We need to rediscover the first breath. From 1937, at the same time as painting, Bazaine worked on making stained-glass windows, a technique which he always found fascinating and which he continued to perfect. Although he gave a model to the master glassmaker, he executed life-size lead drawings and chose, one by one, the ochres that he painted using the medieval process of ‘grisaille’. From 1947, the year in which he met Père Couturier, he participated in the revival of sacred art, which corresponded to his artistic and spiritual ideas, with his friends Manessier, Elvire Jan and Le Moal. Between 1943 and 1947 he made three stained-glass windows for the church of Assy (Haute-Savoie). In 1951 he executed the first mosaic for the facade of the church of Audincourt (Doubs). In 1954 he made two stained-glass windows in slabs of glass for the baptistery of the church of Audincourt and, in 1958, a window for the church of Villeparisis for the reception centre for the homeless at Noisy-le-Grand. In 1964 he made a series of eight windows for the church of Saint-Séverin in Paris (finished in 1970). Finally he participated in a group commission for windows for the cathedral of Saint-Dié. In 1960 he made a mosaic for the liner France and in 1963 and a mosaic for the Maison de l’ORTF (Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française). Towards the end of his life he completed two monumental works: a mosaic fresco for the Sénat in Paris (1987), and the mosaic for the vault of the Cluny–Sorbonne metro station in Paris (1988).

Another activity retained Bazaine’s interest: set designing. In 1951 he designed the sets and costumes for the Comédie de Saint-Etienne, and in 1952 costumes for a ballet by Janine Charrat: Massacre des Amazones. From 1967 he made tapestries. From 1944 he illustrated a large number of works of poetry.

After obtaining a degree in literature, Bazaine studied at the Beaux-Arts in Landowsky’s studio, but gave up sculpture to attend painting classes at the Académie Julian. He made friends with Gromaire and Lhote, and showed his work for the first time in 1930 at Jeanne Castel’s gallery with Fautrier and Goerg. After his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Van Leer in Paris in 1932, he regularly exhibited in the capital, notably at the Galerie Maeght from 1949: Peinture de 1943 à 1949, (Derrière le miroir texts by H. Maldiney and A. Frénaud); 1953 Trente Peintres de 1950 à 1953 (Derrière le miroir, text by M. Arland): 1957 (Derrière le miroir, text by A. Frénaud), exhibitions which continued until the end of his life.

Outside France, the Sandinavian countries always reserved the best welcome for Bazaine’s work. From 1946 to 1947 he exhibited with Lapicque and Estève at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, then in Copenhagen and Stockholm, where he had his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Blanche in 1950, followed by a second in 1964.

From 1956 to 1958 he stayed each summer at Zeeland, which inspired him to make an album of drawings and watercolours: Hollande, published by Maeght in 1962 with texts by Jacques Tardieu.

His first retrospectives took place in 1959 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Stedelijk Abbemuseum in Eindhoven and the Kunsthalle in Bern, followed by those of 1962 at the Kestner-Gesellschaft in Hanover, the Kunsternes Hus in Oslo and the Kunsthaus in Zurich. He had an exhibition of watercolours and drawings at the Galerie Bendor in Geneva in 1958.

He participated in numerous group exhibitions: 1948–1952 Venice Biennial. 1951 1st Sao Paulo Biennial and in 1953. He exhibited on several occasions at the International Exhibition of Painting at Pittsburgh in 1950 (he obtained a second distinction), 1955 and 1958.

In 1952, invited as a member of the jury by the Carnegie Foundation, he visited the USA for the first time. The gigantic scale of this country had a considerable influence on his work, as did Spain, which he visited between 1953 and 1954 and in 1962.

Kassel Documenta in 1955 and 1959.

Bazaine took part in a number of exhibitions of French painting outside France: 1949 La Nouvelle Peinture française, which toured Europe, Canada and Brazil; Tendances Actuelles de l’École de Paris in 1952, Kunsthalle, Bern; and Younger European Painters, Guggenheim Foundation in New York in 1954. In 1961 he travelled to Moscow for the Exposition d’Art Français. He gave a talk on ‘La peinture et le monde aujourd’hui’, which was a considerable success despite opposition from the authorities. He renewed the experience in 1962 in Bucharest and in 1966 in Prague.

In Paris, he showed at the Salon de Mai from 1949 to 1951 and in 1952, and took part in l’École de Paris at the Galerie Charpentier from 1954 to 1957.

The Galerie Louis Carré organised Peintures 1942–1947 in 1965.

The Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris held a retrospective in the same year. Catalogue by B. Dorival.

1964: Bazaine was awarded the Grand Prix national des Arts.

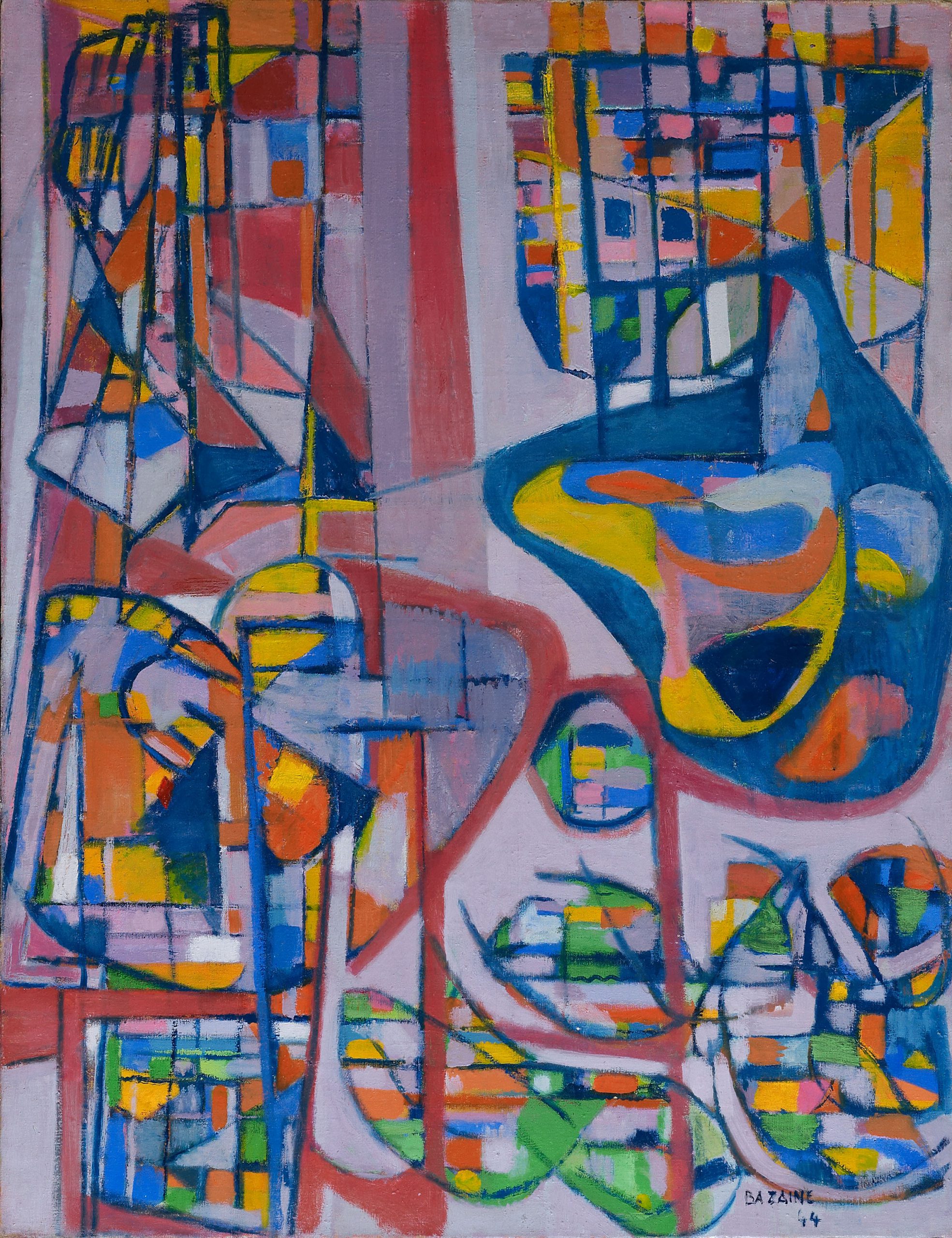

Bazaine’s world is constantly evolving. He speaks to us about our roots, about what is buried deepest within ourselves. A breath has carried away – torn up, one could say – the structural grid of lines that characterised his paintings until about 1955 to 1958, to free colour, giving it all its quintessence and allowing it to breathe. The coloured strokes now mingle with violence, simulating arabesques, with bursts of light. The richness of his palette, with its very subtle shades, so delicate with their musical resonance, often in blues and reds. Today red seems uppermost, the most intense colour, and purplish red. A lyricism whirls round forms and colours like spray sweeping the shore, where violent waves open onto an endless horizon of limitless possibility. Bazaine restores for us ‘nature’s gesture’.

Among the many exhibitions and retrospectives, we should mention:

1977 Bazaine. Musée Beaux-Arts, Rouen. Catalogue.

1977–1978 Œuvres récentes et tapisseries. Musée Metz. Catalogue.

1987 Retrospective Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul. Catalogue.

1988 Bazaine. Dessins 1931–1988. Musée Matisse, Le Cateau-Cambresis. Catalogue.

1990 Retrospective. Grand Palais, Paris. Catalogue, complete biography and bibliography, Skira.

Recent exhibitions at the Galerie Adrien Maeght, Paris: 1987, Chants de l’aube. Catalogue. 1988 Early works.

1991 Recent Works. Galerie Carré et Cie, Paris. Catalogue.

Bazaine’s work is represented in a large number of museums in France and abroad.

- Le temps de la peinture: réunion de Notes sur la peinture, d’aujourd’hui and Exercice de la peinture, with several articles. Aubier, 1990.

- Jean Tardieu, Jean-Claude Schneider. Viveca Bosson: Bazaine, monographie. Adrien Maeght, 1975.