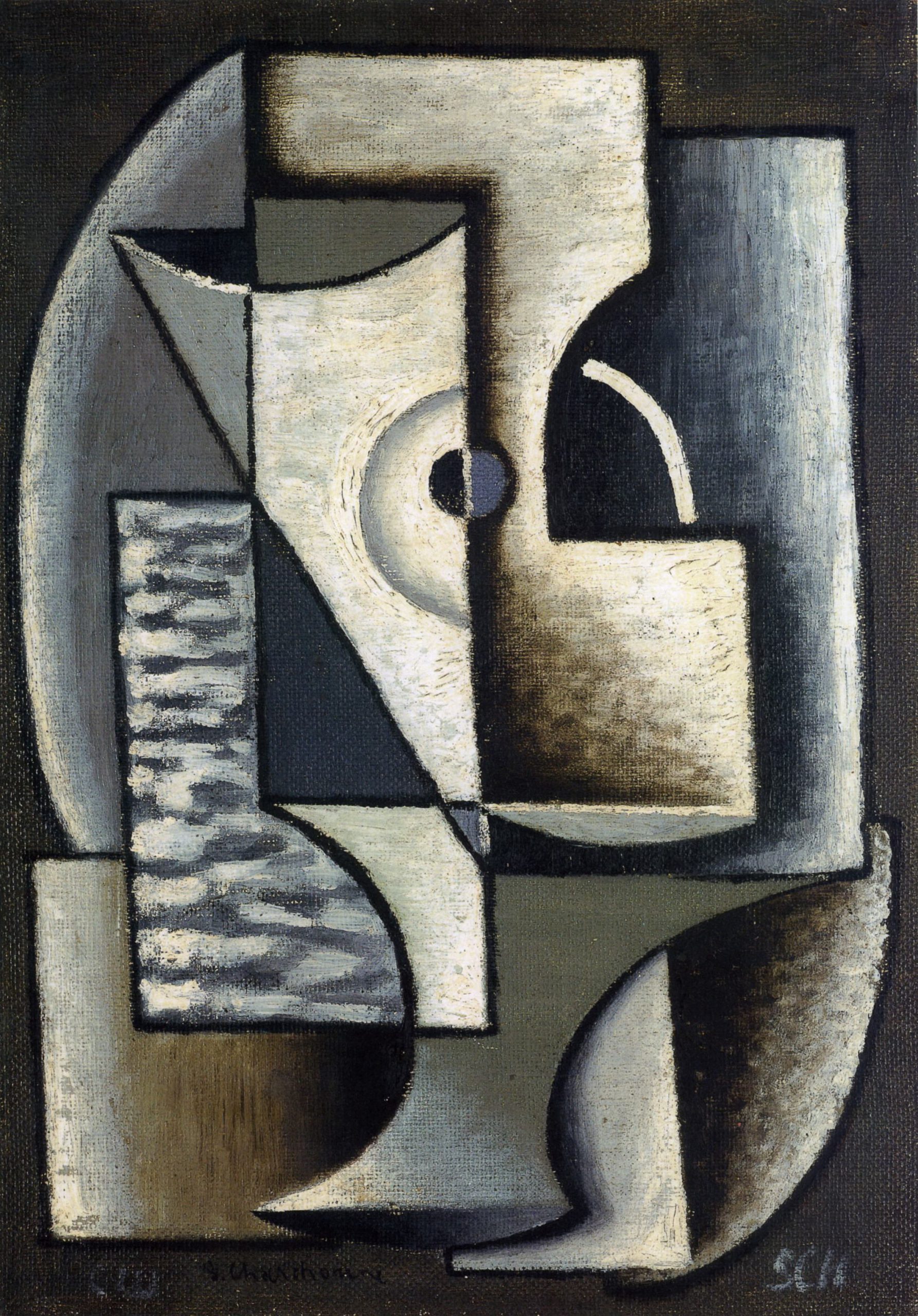

In 1927 Nadia Léger introduced Charchoune to Ozenfant, whose purism influenced him for a while. Ozenfant wrote a text for Charchoune’s exhibition at the Galerie Aubier.

Charchoune gave up purism and began working on various series, in which a Dadaist inspiration was again apparent: Les paysages élastiques and L’impressionnisme ornemental (1929–193l). Charchoune had found his path. A mystical character began to appear in his works, asserting itself during a period of poverty dictated by the great economic crisis (1932–1942). In 1942 he obtained a studio in the Cité Falguière, where he lived until 1960.

In 1944 Edwin W. Livengood offered him his first contract and, in 1945, Charchoune began working with the Galerie Raymond Creuze, with which he exhibited for 12 years: in 1944 (from 1946 to 1948 the violin became a new expressive vehicle anticipating the musical series), 1947, 1948 peintures de 1926 à 1931, 1949 cycle marin with the reappearance of colour, 1951 œuvres récentes, 1952 Charchoune, Venise, 1956 Œuvres récentes.

In 1954 and 1955 Charchoune was inspired by the writing of Kafka to make his series Métamophoses. Although since 1912 he had been in regular attendance at the Colonne concerts, it was not until after 1956 that music became the sole medium of his work: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Tchaikovski provided him with his “fuel”. Intentionally, he gradually erased from his palette the earlier explosions of colour, favouring shades of ochre, often austere monochromes and shades of white, from which emerged curves, signs and furrows, whose undulation from left to right recalled his relationship with water and music. He achieved a sobriety, where expressiveness and spirituality appear from the rich sensual texture. “Music gives me the subject. Listening to music, I can see the painting with my eyes closed, like a coloured thread unwinding, I see it first with primary colours and my painting starts out as very colourful. I listen and make telepathic marks on the canvas. It becomes ornamental. I begin to spit colour and it becomes decorative, very colourful” (interview with Michel Ragon, Jardin des Arts, September 1966). His impatient desire to express is feelings on canvas while listening to music led him to structure his composition with a sophisticated arrangement of brush strokes that achieve a synthesis in this series of works. In no way abstract, they have generous areas of pure painting, simultaneously luminous and sonorous. This is painting to enjoy and reflect on, but it has always had a limited success with the public, although his colleagues expressed their admiration. Jacques Villon: “I am delighted that I will soon be sharing your elegant sober work”(1941), Nicolas de Staël, who every day contemplated the small painting which hung in his bedroom, Hosiasson: “What can one say about Charchoune who seeks the inexpressible…? Colour – when he uses it – is emptied of all resonance: his painting is inspired by murmurs… Whoever has glimpsed it will be unable to forget it” (1957), and Picasso: “For me, there are two artists: Juan Gris and Charchoune”. Nonetheless it is the adjectives “forgotten”, “unrecognised” and “ignored” that are emitted from the pens of the most eminent writers and critics: Philippe Soupault, Alain Jouffroy, Charles Estienne, Gaston Diehl and Pierre Schneider… Nevertheless, the exhibitions continued, even though fame was of little importance to the artist, who stated: “I was and I remain a man of nature, but I was also born a man of Art, and these three elements, forest, river, music, rapidly became for me a pictorial harmony which I attempted to put on paper”(op. cit.).

Exhibitions in Paris in 1957, Galerie J.C. de Chaudun (catalogue) and Galerie Dina Vierny.

1958 Galerie Michel Warren, text by Patrick Waldberg. 1960 Galerie Henri Bénézit, Galerie Georges Bongers and Galerie Jacques Péron.

1961 Galerie Cahiers d’Art.

Georges Bongers showed his work again from 1966 to 1967.

1970 Galerie Jean-Louis Roque, text by Pierre Brisset, and again in 1971, when he showed watercolours.

He illustrated several works of literature.

1970–1971 First retrospective at the Musée Saint-Denis in Reims, followed in 1971 by the Musée National d’Art Moderne. (Catalogue Archives de l’Art Contemporain no. 18, preface by Jean Leymarie and several texts.)

1974 Galerie de Seine, Charchoune, harmonies blanches 1924–1974. Catalogue, text by Alain Bosquet, documentation by René Guerra.

Abroad he exhibited in New York (1960), Germany, Italy, Geneva and Luxembourg.

Among the main group exhibitions: 1948 École de Paris, Boulogne-sur-Mer. 1951, Peinture d’aujourd’hui, Palazzo Belle Arti, Turin: France-Italie. 1952 L’École de Paris, Librairie Hachette, Montreal. 1956 Dix ans de peinture française 1945–1955, Musée de Grenoble. 1957, Cinquante ans de peinture abstraite, Galerie R. Creuze; Art abstrait, Musée de Saint-Etienne. 1963 La grande aventure de l’art du XXe siècle, Château des Rohan, Strasbourg.

Charchoune participated in the Salon Comparaisons from 1956 to 1961, at the Salon de Mai since 1960 and at the Réalités Nouvelles in 1956 with 7e symphonie de Beethoven, in 1957 with Concerto pour piano de Tchaikovski and from 1958 to 1963. He was given a tribute in 1976.

1980–1981 S. Charchoune peintures 1913 à 1965. Musée de l’Abbaye Sainte-Croix, Les Sables-d’Olonne. Catalogue, Cahiers de l’abbaye no. 39, Henri-Claude Cousseau, Michel Seuphor.

1981 S. Charchoune œuvres 1913–1975, Galerie des Ponchettes, Nice. Catalogue, text by Michel Seuphor.

1988 Charchoune œuvres de 1913 à 1974, Galerie Fanny Guillon Laffaille, Paris. Catalogue, text by Patricia Delettre. Biography, bibliography.

1989 Charchoune, Centre culturel de la Somme and Musée départemental de l’Abbaye de Saint-Riquier. Catalogue by P. Delettre.

Museums: Alès – Charleville – Dijon – Grenoble – Les Sables-d’Olonne – Nice – Paris, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou and Ville de Paris – Pontoise – Reims – Roanne – Saint-Etienne – Strasbourg – Villefranche-sur-Mer – Villeneuve-d’Ascq and abroad.

Raymond Creuze: Charchoune, R. Creuze, Paris 1975–1976, 2 vol. Catalogue raisonné of the paintings in preparation by Patricia Delettre.