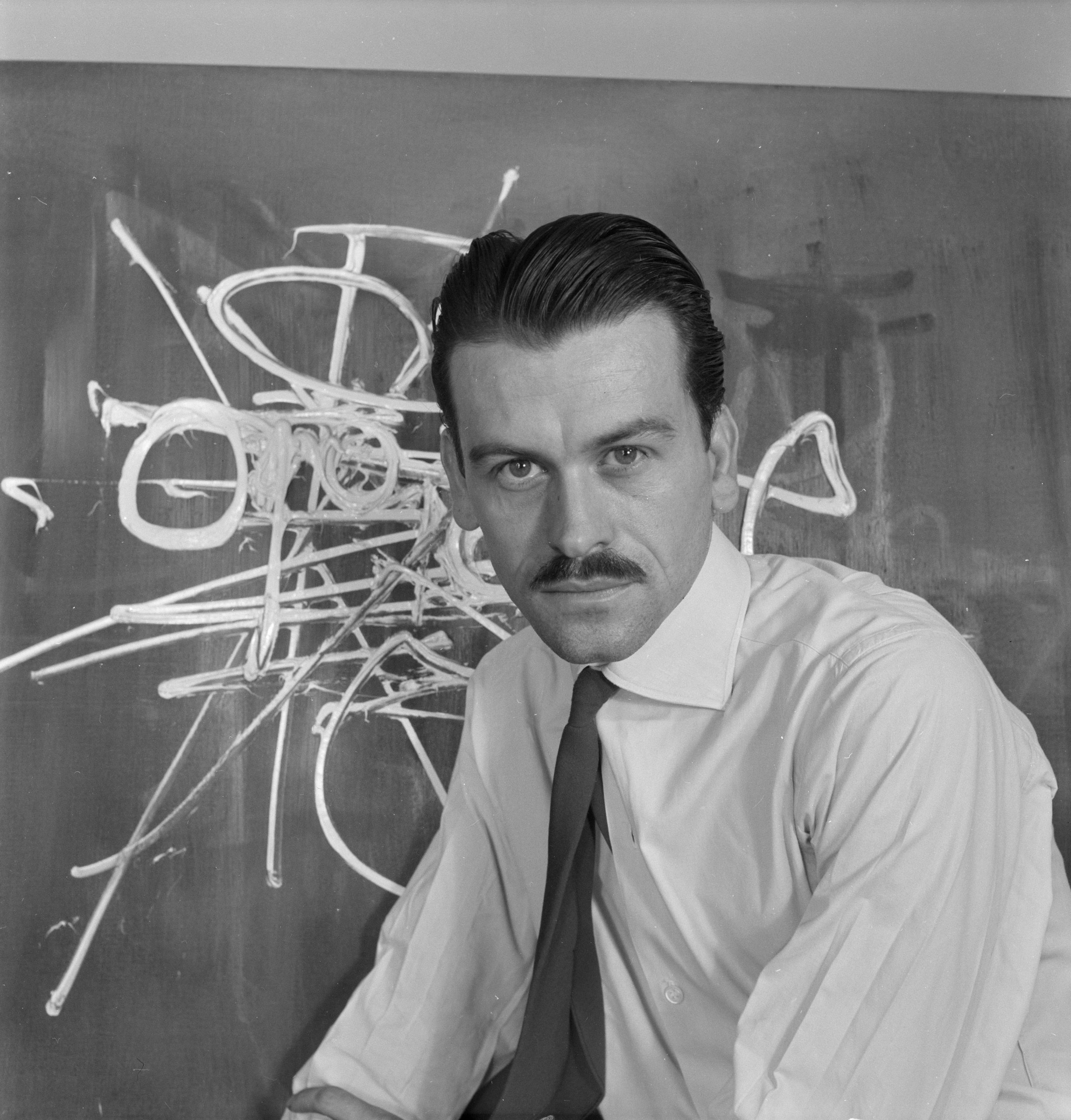

Georges Mathieu

1921 - 2012

A master of lyrical abstraction, to which he admitted being the instigator, his plastic and philosophical experience was at the source of the formal upheaval in the world of painting following the Second World War. By being the first to react violently against geometrical abstraction, he installed a mode of expression – a ‘language’, as he put it, which would determine the most creative and revolutionary movement until the return of new figuration in the 1960s. By favouring the sign as a metaphorical image, indissociable from the gesture, speed was at the heart of his creative activity and identified with its function, which is notably to embody signs. He represented a phenomenon hitherto unknown, based on the aesthetics of speed, and consequently, of risk. The picture plane opens to a series of signatures, like a furious multitude of gestures endowed with considerable expressive power.

Improvisation and spontaneity determine what can be described as a calligraphic choreography, where the notion of time-play participates in destroying the image to restore the essential. Contrary to the definition of traditional painting which, according to Aristotle, is a “representation of an action,” Mathieu identifies painting with action itself. Having created a spiritual vacuum, he sets his expressive potential free which, through the agency of the gesture, combines with his energy potential.

“ By favouring the sign as a metaphorical image, indissociable from the gesture, speed was at the heart of his creative activity and identified with its finality, which is notably to embody signs. He represented a phenomenon hitherto unknown, based on the aesthetics of speed, and consequently, of risk. The picture plane opens to a series of signatures, like a furious multitude of gestures endowed with considerable expressive power. ”

The Mathieu d’Escaudœuvres, bankers, originated from Cambrésis. Through his mother, Madeleine Duprés d’Ausque, he descended from Godefroy de Bouillon. As a young boy he was a brilliant pupil in his private schools: he participated in the Concours Général for French at Cambrai (1937–1938) and mastered Greek, Russian, Spanish and English. He took a bachelor’s degree in French literature and enrolled at the Cambrai’s Law Faculty, where he had returned upon his father’s death in 1941.

In 1942 he began painting from coloured postcards of London: for example Oxford Street by Night and Portrait of Margaretta Scott. Appointed teacher of English at the Lycée de Douai, he also became an interpreter for the American army in Cambrai. Self-taught, his knowledge of contemporary painting was very slight. He broke with conventional pictorial and sensitive heritage after reading Edward Crankshaw’s study of Joseph Conrad, Conrad’s Craftmanship, influenced his first non-figurative works. His commitment to dismissing figurative painting was total.

It is no doubt necessary to dispel any ambiguity that might be associated with his approach: although he repudiated any form of conservatism, including even the slightest reference to nature or to a geometrical repertory, which he considered the ultimate interpretation of the doctrines derived from the Renaissance, he was aware of the past’s importance and was content to cultivate its grandeur. He also retained traditional materials: canvas, oil, colours and brushes. There is therefore no destruction, but rather a confrontation with plastic laws, which he considered to be obsolete.

Huile sur toile

160 x 400 cm

Without resorting to the conceptual, formal or significant, Mathieu discovered a world beyond meaning. “Freedom is emptiness,” he wrote for the HWPSMTB exhibition in 1948. He painted his first paintings, unfinished and allusive. Stridence (1945) is informal, and Evanescence (1945) is a first ‘dripping’, which already anticipated the intertwined forms of Pollock. Both artists painted with the canvas laid flat on the ground. The artist’s gesture consists of allowing the liquid colour to flow, and this achieves a certain formal similarity: predominance of curves, superimposed drippings, absorption of the substance by the form. In 1946, on his return from the American University in Biarritz where he had been teaching French, he worked alone in the countryside, in particular at Istres (Bouches-du-Rhône), where he lived with a Monsieur de Saint-Marty. He began a correspondence with René Guilly. He sent his work Scène macabre to the Salon des Moins de Trente Ans and, in 1947, showed three paintings at the second Salon des Réalités Nouvelles: Survivance, Conception, Désintégration. In October that year he showed two recent works at the 14th Salon des Surindépendants, Exorcisme and Incantation, which were remarked upon by the critic Jean-José Marchand, who found them “very lyrical, extremely moving, capable I believe of affecting the public even though they ‘do not represent anything’ ” (Combat, 16 October 1947).

Compared to geometrical constructivism and neoplasticism, Mathieu’s work was disconcerting. Living in Paris, where he was responsible for public relations for the American shipping company United States Lines, he became aware of the profound originality of lyrical abstraction and began to become its advocate. He observed important similarities between his approach – based on emotion and removed from all rationalism – and that of artists such as Hartung and Wols (whom he met practically every evening until the latter’s death in 1951), and equally those of Atlan and Bryen, whose experiments were close to his own, deciding to link his destiny to theirs. Driven by a proselytising spirit, he energetically devoted himself to imposing “an abstraction which is not enclosed by rules, dogmas or canons of beauty, an open abstraction, that is free” (Mathieu, Au-delà du tachisme, Julliard, 1963).

For this purpose he met as many people as possible at exhibitions who had both similar and different opinions to his own. Before considering a one-man exhibition of his own work, he wanted to “find the means to proclaim a truth that has been obsessing [him] for three years” (Paris, 1947). He continued: “I do not meet anybody who seems to feel even vaguely that we are witnessing a special moment, a liberating ascension. It is not at all a matter of preparing a mad maelstrom of destruction or self-destruction of the forms preceding our culture, rather that we must introduce in the West ‘the advent of a new awareness of being, a new freedom and a new history of the world’ ” (op. cit.).

L’Imaginaire was the first of these events to contest geometrical formalism, and it officially inaugurated lyrical abstraction. The exhibition was held at the Galerie du Luxembourg, at number 15 rue Gay-Lussac, run by Eva Philippe. Mathieu brought together there Bryen, Hartung, Atlan (whom he met almost daily and with whom he had long conversations), Wols, Arp, Riopelle, Leduc, Verroust who was invited by Jean-José Marchand (who wrote the presentation preface titled Abstraction lyrique), Ubac, Vulliamy, Brauner, Solier and also Picasso, who showed a non-figurative drawing.

It was at the request of Colette Allendy, who wished to organise a similar new group exhibition, that in April 1948 the exhibition HWPSMTB was held at her gallery in rue de l’Assomption. The initials were those of the names of each of the participants: Hartung, Wols, Picabia (who had returned to abstraction), Stahly, Mathieu, Michel Tapié and Bryen. The catalogue included texts by the artists, except for Hartung and Stahly, who did not contribute. In Paru (June of that year), Jean-José Marchand writes about ‘pictorial lyricism’. In July of the same year there was also White and Black, a first exhibition of black-and-white drawings, prints and lithographs, held at the new Galerie des Deux-Isles opened by Florence Bank. The exhibition included works by Hartung, Wols, Arp, Tapié, Picabia, Ubac and Germain. Edouard Jaguer and Michel Tapié provided texts for the catalogue.

Finally, in November 1948 Mathieu organised the first confrontation with American painting, at the Galerie du Montparnasse, which made it possible to discover the new trends of that country’s avant-garde and the works of Pollock, Tobey, de Kooning, Gorky, Reinhardt, Rothko, Russell and Sauer (unknown in Paris), shown alongside those of Bryen, Hartung, Picabia, Wols and Mathieu. Léon Degand remarked: “These Americans belong to the École de Paris.” Mathieu participated for the last time in the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. In March 1949 Mathieu wrote Analogie de la non-figuration, published by R. Fournier and reprinted for Véhémences confrontées and his New York exhibition in 1952. These texts, together with a number of later writings, were included in his book De la Révolte à la Renaissance (Gallimard, 1973). He took part in group exhibitions at the Galerie René Drouin, notably in Huit œuvres nouvelles with Dubuffet, Fautrier, Maria, Matta, Michaux, Ubac and Wols in July and August. In November he exhibited with some members of the group (Michaux, Ubac, Wols) in New York at the Perspective Gallery.

Between 1948 and 1950 Mathieu invented his signs and mastered the ‘language’ of his lyrical gesture marked by speed and spontaneity, an expression of his entire being, generating energy. In 1950, he painted the first ‘tachist’ paintings. After a group exhibition titled Seize peintres at the Galerie Drouin, Mathieu had his first solo exhibition, at the same gallery, an exhibition which lasted two days! (22 and 23 May). Eight paintings were shown for the launch of a book of poems by Emmanuel Looten, Complainte sauvage, which the artist illustrated with signs: Pertre, Atrassonance, Règne Blanc and Hommage à Louis XI were some of the works praised in a text by Jean Caillens titled Hiroshima, place Vendôme. The originality of Mathieu’s approach was acknowledged by a wide spectrum of opinions, including Sir Herbert Head, Henri Michaux, Stéphane Lupasco and André Malraux, who exclaimed: “At last a Western calligrapher!” Mathieu replaced his shaded backgrounds with uniform backgrounds and more independent signs. He observed that “ ’Calligraphy’, by essence an art of signs, has freed itself from the literal significative content of writing to be only the direct power of meaning” (op. cit.). The Galerie Drouin closed at the end of 1950 with the prestigious exhibition Pour un art de vivre, which included works by Toulouse-Lautrec, Lucas Cranach, Max Ernst, Kandinsky and Mathieu.

The avant-garde sought refuge in new galleries. The Galerie Nina Dausset presented an ultimate confrontation with Mathieu, in March 1951, with Véhémences confrontées. The group of French, Italian and American artists included Bryen, Capogrossi, de Kooning, Hartung, Pollock, Riopelle, Russell, Wols and Mathieu, who designed the manifesto poster: texts in red on the back, by each of the participants, surrounding a passionate text by Michel Tapié, and reproductions of works and drawings in black on the front. He wrote two texts, one on Les rapports de la Gestalt-théorie et de la non-figuration, in which he demonstrated that the sign precedes meaning, and the other on La pseudo-dualité du Moi.

Pierre Loeb commissioned six paintings from Mathieu, and at the same time became his second dealer. Mathieu wrote Esquisse d’une embryologie des signes (in De la Révolte à la Renaissance), an argument which, while justifying what was to be known as ‘informal’, simultaneously condemned it, convinced that the future for a new form of art involved L’incarnation des signes (text used again by Mathieu for a lecture in Paris in 1956). In 1952 he painted at the Studio Facchetti, which also showed his first two large canvases, Hommage à Philippe III le Hardi and Hommage au Maréchal de Turenne, “in which I am probably the first to have used more ‘systematically’ than anyone else stains in their most ‘basic state’ ” (op. cit.). Preface by Michel Tapié Le message signifiant de G. Mathieu.

It was Henri Michaux who, around 1950 or 1951, pointed out to him the similarities between his own technique and that of oriental drawing. A solo exhibition was held in New York at the Stable Gallery organised by Alexandre Iolas, who bought 18 paintings. He wrote Déclaration aux peintres d’avant-garde américains, which closes with: “Give a meaning to new signs, reinvent signs” (in De la Révolte à la Renaissance).

In April 1953 Mathieu showed seven paintings at the Galerie Marcel Evrard in Lille. In May the publication of Premier bilan de l’Art actuel by François Didio was accompanied by a series of events at the Galerie Arnaud, the Galerie Jeanne Bucher, the Galerie Craven, the Galerie Nina Dausset, the Galerie La Hune, the Galerie Denise René and an important seminar attended by artists and critics at the Salle de Géographie in which participated Atlan, Baskine, Lapoujade, Dewasne, Mathieu (speaking on 9 June 1953) and J. Bouret, L. Degand, R.V. Gindertaël, Michel Tapié, and J. Lassaigne, among the 25 art critics who had been part of this appraisal. Mathieu then prepared the first issue of a bilingual journal the United States Lines Paris Review, which he was to edit for 10 years, published by Marcel Coudeyre (Paris). The issues considered the new currents in Western civilisation, relations between art, science and ideas, the notion of play (1956–1957), the sacred, dandyism (1962–1963), celebration (1960–1961) and humour (1955).

In 1954 Mathieu had a solo exhibition at the Kootz Gallery in New York. He painted La bataille de Bouvines, shown at the Salon de Mai, and for this occasion also made a film with Robert Descharnes, which was followed by Les Capétiens partout, painted in Jean Larcade’s château at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, in which intense fury contrasts with the marked lyricism of his ‘Zen’ paintings, such as Godefroy de Bouillon (1952), Adam du Petit Pont (1954) and later Hommage à Louis IX (1957) and La Bulle Omnium datum optimum (1958), made with a single gesture in only a few seconds, or Clovis fils de Dagobert (1960) and Vez (1964).

In the two modes of expression, the act of painting becomes part of a ritual which revives the prestige of the sacred. Les Capétiens partout was shown with 14 earlier paintings at the Galerie Rive Droite in November, with catalogue introductions by Stéphane Lupasco and Mark Tobey. The exhibition demonstrated the different approaches employed by Mathieu, who only required from technique that it serve his purposes: ‘dripping’, which consists of allowing the liquid paint to flow straight onto the canvas. Because of paint’s consistency, this process precludes any straight lines. In 1957 and 1958, he used chrisochrome in a wager, its liquid character obliging him to paint even faster. ‘Tubisme’, the technique which, by reducing the gap between gesture and mark, precludes hesitation and closely relates drawing to colour. Mathieu recounted the origins of the word ‘tachism’: “It has been taken from the enemy,” exclaimed Charles Estienne. The enemy was Pierre Guéguen, who had indeed used the word for the first time in 1951 during a lecture given at Menton on abstract art, which Estienne had ridiculed in the October–November 1953 issue of the review Art d’aujourd’hui (op. cit., pp. 88–89). In August Mathieu showed several gouaches at the Zoé Dusanne Gallery in Seattle and, at the end of the year, he had two solo exhibitions in New York of paintings made between 1948 and 1951 at the Alexandre Iolas Gallery and the Kootz Gallery.

During this period, Mathieu participated in important group exhibitions: in 1951, Signifiants de l’Informel at the Studio Facchetti, organised by Michel Tapié, who chose three figurative artists – Fautrier, Dubuffet and Michaux – and three non-figurative artists – Mathieu, Riopelle and Serpan. For Mathieu, it was nonsense to associate the two terms in the exhibition’s title. This confusion was prolonged by Michel Tapié in June 1952, with the second part of this exhibition, which included eight lyrical abstraction artists: Bryen, Donati, Gillet, Philippe Martin, Mathieu, Pollock, Riopelle and Serpan, and not a single figurative artist. In June of the same year, Michel Tapié presented, once more at the Studio Facchetti, Peintures non abstraites, which this time did include figurative artists: Appel, Glasco, Ossorio, Arnal, Guiette, Pollock, Dubuffet, Michaux and Ronet (who became a film actor).

Lastly, in December 1952 the term ‘informel’ changed to ‘autre’. Studio Facchetti exhibited Art autre, with the works of the two aforementioned groups, accompanied by a book (published by Gabriel Giraud) with the same title and in which were reproduced all the aforementioned artists, but with the addition of Brauner, Maria, Sironi, Marini, Hofmann, Paolozzi, Dova, Butler, Baskine, Richier, Sutherland and Matta, under the patronage of Picabia and Duchamp. This ambiguity was overlooked with Individualités d’aujourd’hui 1 in October 1954 at the Galerie Rive Droite, where Tapié showed 27 artists, and in January 1955 at the same premises with Signes autres (l’Aventure informelle, ref. la Révolte à la Renaissance, op. cit.).

There were several further group exhibitions: 1952 Le Génie de Paris, Pavillon de Marsan, Paris; Galerie Pierre, Paris and again in 1953; Cercle des Arts, Paris; Kunsthaus Zurich. 1953 Six painters at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London; Young European Painters organised by James J. Sweeney at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. 1954 European Painters at the Downtown Gallery in New York; Caratteri della pittura d’oggi at the Galleria de Spazio in Rome. 1955 Retrospective of the First Lyrical Abstract Painters at the Kunsthalle in Bern and Individualita d’Oggi at the Galleria de Spazio in Rome.

From 1956 Mathieu, who had always travelled, began making an increasing number of visits to Japan, the USA, South America, the Middle East and various European capitals to confront the plastic upheaval represented by lyrical abstraction with the different manifestations of the avant-garde, in aesthetics, philosophy, linguistics and science. Each country that he visited became the location for the creation of a series of paintings, generally with large dimensions: Série des batailles, La bataille d’Hastings in England (1956), Les Batailles d’Hakata et de Gowa in Japan (1957), Milwaukee in the USA (1957), La bataille de Brunkeberg in Sweden (1958), L’abduction d’Henri IV in Germany (1958), L’hommage au Connétable de Bourbon accompanied by ‘musique concrète’ (concrete music) composed by Pierre Henry in Vienna (1959), Macumba in Brazil (1959), L’hommage au général San Martin in Argentina (1959), Guggemusik in Switzerland (1961), Saint Georges terrassant le dragon in Lebanon (1961) and La bataille de Gilboa in Israel (1962). These works were sometimes painted in public in front of hundreds of spectators. This act became part of a ritual in which risk was total and inspiration the priority, to free uncontrolled emotion in the shared joy of play and creation.

In 1956 24 works were exhibited from the Epistémologique period of the previous year including Théorème d’Alexandroff and Entropie négative restreinte at the Kootz Gallery in New York. On 27 February Mathieu gave a talk at the Centre International d’Études Esthétiques: Vers une nouvelle incarnation des signes. On 11 March he executed four wall paintings, Hommage au Prophète Elie, at the Centre d’Études Carmélitaines in Paris. In May, for the Nuit de la Poésie, a part of the Festival International d’Art Dramatique de Paris, he for the first time painted in public what remains his largest canvas (12 m x 4 m) on the stage of the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt Hommage aux Poètes du Monde entier. A solo exhibition of the paintings called Post-capétiennes and Carolingiennes, and a presentation of Couronnement de Charlemagne against a gold background at the Galerie Rive Droite. For this exhibition, he made another film with Robert Descharnes on the relationship between art and play.

At the same time, an exhibition was held of the gouaches done in 1954, 1955 and 1956 at the Galerie Pierre in Paris. In June Mathieu gave a talk with Dr Chou-Ling, the permanent representative of China to UNESCO, attended by the great master Tchang Kta Ts’en, on the subject of Les rapports de la calligraphie extrême-orientale et de la peinture non-figurative lyrique (reproduced in De la Révolte à la Renaissance). A confrontation between East and West took place in November 1958 at the Musée Cernuschi in Paris, with Morris Graves and André Marchand, Foujita and Tal Coat, Mathieu, Tobey and Hartung, Domoto and Zao Wou-ki. Also in 1956, two major solo exhibitions were held in the summer in London at the Institute of Contemporary Art with large canvases including Hommage au Comte de Boulogne, Etienne de Blois (2 m x 4 m), and in November at the Kootz Gallery in New York, with paintings from Période carolingienne, with a catalogue introduction by Igor Troubetskoï. At the same time he participated in Structures en devenir at the Galerie Stadler in Paris.

In March 1957 Mathieu organised with Simon Hantaï the Cérémonies commémoratives de la seconde condamnation de Siger de Brabant at the Galerie Kléber, which aimed to retrace the cultural and spiritual evolution of the West from the Edict of Milan in 313 until 1944. Early in the year he went to Brussels for an exhibition at the Palais des Beaux-Arts of 50 gouaches painted between 1954 and 1956. In Brussels he painted La bataille des Eperons d’or against a background of gold leaf. In Japan he painted 21 paintings in the space of three days in Tokyo for an exhibition prefaced by Shoichi Tominaga and Shuzo Takiguchi. He then painted six paintings in Osaka. In September he gave a talk to 2,000 students organised by the newspaper Asahi on the subject of Western avant-garde painting.

In New York he painted 14 paintings on 9 October, which were then shown at the Kootz Gallery, which a month earlier had given him a solo exhibition with a catalogue introduction by James Fitzsimmons. During this visit, Mathieu gave his only interview in the USA, Art Beyond the Sound Barrier, to the San Francisco Chronicle. In Milan, he painted 12 paintings, including L’incendie de Rome, shown at the Selecta Gallery at the end of December, an event which was preceded by a solo exhibition at the Galleria Naviglio. He gave a talk on the relationship between avant-garde painting and the calligraphies of the Far East. In November, he showed a series of 14 paintings in Brussels with the title Cycle des grands ducs d’Occident at the Galerie Helios Art. In 1957 he also took part in two Paris retrospective exhibitions of the painting of the previous 10 years: Rétrospective at the Galerie René Drouin, and L’Exemplaire at the Galerie Kléber, which subsequently became the Galerie Jean Fournier.

1958 saw several solo exhibitions in Dusseldorf, Stockholm (drawings), Lyons (at the Galerie Grange, presented by Julien Alvard), Basel and Ascona. To celebrate the 840th anniversary of the founding of the Templar Order, he painted seven large works including Bataille de Tibériade on a silver background at the Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain in Paris, which he inaugurated on 4 June. He published a study titled La Nouvelle orientation de la civilisation occidentale in the United States Lines Paris Review. Solo exhibitions were held at the Musée Liège and the Galerie Rive Droite in Paris consisting of gouaches and drawings. He painted 26 paintings in Stockholm at the Hallwylska Museum. Among his participations in group exhibitions were: Art vivant at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Basel; Les origines de l’Art informel at the Galerie Rive Droite, followed by Le dessin dans l’Art magique; Orient-Occident at the Musée Cernuschi; and Pittsburgh International Exhibition at the Carnegie Institute. On 27 November, he gave a talk on L’Avenir de la peinture non-figurative in Brussels at the Palais des Beaux-Arts.

From 1959 onwards major retrospectives were organised: Kunstverein Cologne (paintings from 1944 to 1959); Kunsthalle Basel (works from 1945 to 1958); the Galerie Iolas New York (paintings from 1949 to 1951); the Museums of Neuchâtel (paintings from 1944 to 1958) and Geneva (25 paintings from 1946 to 1958). In Paris he showed 30 gouaches at the Galerie Jacques Dubourg. Retrospective of eight monumental paintings done in Europe between 1954 and 1959 at the Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain. Among the group exhibitions were Actualités at the Arthur Tooth Gallery in London; Twenty Contemporary Painters Coll. Dotremont, Guggenheim Museum, New York; Dix ans d’activité Galerie Paul Facchetti, Paris; Young Painters of Today Kunstlerhaus, Vienna; L’École de Paris dans les collections belges Musée national d’Art moderne, Paris; Itinéraire d’un jeune collectionneur Galerie Kléber, Paris; La peinture actuelle Galerie Arnaud, Paris. Abroad, there were solo exhibitions at the San Babila Gallery in Milan, as well as a talk titled De l’Abstrait au Possible; at the Krefeld Museum; and at Kootz Gallery, New York, with 14 paintings as a Tribute to Presocratic Philosophers.

He exhibited in Buenos Aires and gave a talk at the Law Faculty entitled Nouvelles convergences de la science, de la pensée et de l’art occidental and a second talk at the Museum Situation de l’abstraction lyrique. He created a wall painting 63 metres long for the Bal des petits lits blancs at the Foire de Paris, titled Hommage à Charles VI en souvenir du bal des Ardents, and a mosaic for the Ravenna Museum Hommage à Odoacre.

He wrote D’Aristote à l’Abstraction lyrique, a text on the origin of painting salons, which was received as a manifesto when it appeared in the April 1959 issue of the review L’Œil, for which he designed the cover (cf. complete version in De la Révolte à la Renaissance), and wrote other texts such as Les Salons, origine et décadence in Cimaise no. 45–46 1959 (op. cit.)

In 1960, during a stay at Gstaad, he wrote De la dissolution des formes, which appeared in Arguments no. 19 (op. cit.). This was followed by L’autopsie de l’art figuratif for Combat on 7 March 1960. Lastly, on the subject of writing, Mathieu squared off with André Breton. The quarrel between him and the Surrealist master was buried by a virulent manifesto, La monnaie du pape, which clarified once and for all the relations between Surrealism and Lyrical Abstraction. The polemic went back to 1957 and the commemorative ceremonies for Siger de Brabant. Along with 35 other surrealists, André Breton had signed a tract titled Coup de semonce against Mathieu, Hantaï and S. Lupasco, to whom an important tribute had been paid. Mathieu had remained silent. In March 1960, however, after the publication of L’autopsie de l’art figuratif, André Breton demanded from the paper Combat a right to reply. This was to be Riposte on 4 April 1960, signed by 13 directors of surrealist reviews. Mathieu was permitted to print only a part of his reply, on 13 June 1960. He subsequently published a poster, several thousand copies of which were distributed.

He painted a series of large paintings for his exhibition in Paris in May at the Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain under the title De quelques pompes et supplices sous l’ancienne France representative of the Période baroque, with a catalogue introduction by Julien Alvard. The exhibitions continued abroad: New York, São Paulo, London and Venice. Among the group exhibitions were American and European Artists at the Kootz Gallery, New York; Affirmations and Noir et blanc at the Galerie Internationale d’Art Contemporain; and Antagonismes at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

In 1961 two major solo exhibitions were held in Paris: paintings and gouaches titled Attila at the Galerie Rive Droite, and gouaches titled Petites improvisations at the Galerie Jacques Dubourg. He participated in L’Apocalypse at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; Tendances contemporaines at the Galerie Valéry Schmidt in Paris; Lyrisme et abstraction at the Galerie Arnaud; and Alchimie des formes at the Galerie Vanier in Geneva. Exhibitions, in France and abroad, with talks and interviews. A new statement concerning relations between the artist and contemporary society under the title Pour une désaliénation de l’art (in Combat partially on 1 and 15 January 1962, and Arts on 21 March 1962). 1962 solo exhibitions in Basel, Jerusalem, Munich, Turin, Bologna and Tel Aviv. Among the group exhibitions we should mention Antagonismes II and L’objet at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, for which occasion he made a series of sculptures and jewels. Le dessin français du XVIIe au XXe siècle at the Narodowe Museum, Warsaw; Résurgences 1962 at the Galerie Breteau, Paris; and Mostra del École de Paris at the Galleria Levi, Milan.

In 1963 his first Paris retrospective was held at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (catalogue texts by René Héron de Villefosse and Marie-Claude Dane, with complete biography and bibliography). He painted a wall painting (20 m x 3 m) titled Hommage à Jean Cocteau, who had recently died. In 1960 the poet had written the introduction for his exhibition at the New London Gallery in London. He stopped painting for a year, and in 1964 recommenced with small works that he showed at the Galerie Argos in Nantes. In 1965 he showed 100 paintings at the Galerie Charpentier in Paris. On this occasion he gave a talk about the recognition of spiritual values and rebuilding the world modelled on lyrical abstraction. The catalogue is prefaced by Raymond Nacenta, Georges Schehadé and François Mathey.

An ardent militant and man of his time, Mathieu extended his activities to different aspects of daily life. In 1962 he took up sculpture, and in 1964 he took part in preparing the new village of Castellaras in the South of France. After 1965 there were orders from the Manufactures des Gobelins and Sèvres, and he also took an interest in numismatics.

In 1975 he was elected a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

His exhibition at the Galerie Protée in Paris in 1988 was his 170th solo exhibition.

Mathieu’s work is present in 79 museums throughout the world. For France we may mention in Paris the Musée National d’Art Moderne, the Musée Municipal de la Ville, CNAC, Maison de la Radio, Musée Monétaire, Bibliothèque Nationale; – Antibes – Boulogne-sur-mer – Colmar – Grenoble – Lille – Lyons – Toulouse – Dijon – Dunkerque – Limoges – Orléans – Villeneuve-d’Ascq – Le Mont-Doré – Château de Vascœuil.

1978, Mathieu oeuvres monumentales 1963 à 1978, a major retrospective with a series of articles and talks. Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris. Catalogue.

1985 Mathieu, Palais des Papes, Avignon. Catalogue. Text by G. Xuriguera: L’œuvre picturale de Georges Mathieu.

1987 Mathieu. Galerie Sapone, Nice. Catalogue, prefaces by G. Xuriguera and P. Dehaye. Jalons de révolution de l’abstraction lyrique.

1990 Mathieu. Oeuvres monumentales 1958–1978 and Peintures récentes 1989–1990. Abbaye des Cordeliers Châteauroux. Catalogue, text by Jean-Marie Tasset: Mathieu le Barbare.

1992 Hommage à Mathieu. Château-Musée Boulogne-sur-Mer. Book-catalogue, text by Patrick Grainville.

Texts by Georges Mathieu:

- De la Révolte à la Renaissance. Coll. Idées, Ed. Gallimard 1973.

- L’abstraction prophétique, Coll. Idées, Gallimard, 1984.

- De l’abstrait au possible, Cercle d’Art Contemporain, 1959 (preface by René Guitte: Ses demeures).

- Le privilège d’être, Robert Morel, 1967.

- La réponse de l’abstraction lyrique, La Table Ronde, 1975.

- François Mathey: Mathieu, Hachette Fabbri, 1969.

- Dominique Quignon-Fleuret: Mathieu, Coll. Les Maîtres de la peinture Moderne Flammarion, 1977.

Several films including a film by Frédéric Rossif: Georges Mathieu ou la fureur d’être. Télé Hachette, 1971.

Excerpt from L’École de Paris 1945–1965: Dictionnaire des peintres

Ides et Calendes Editions, courtesy of Lydia Harambourg

www.idesetcalendes.com

Official website : www.georges-mathieu.fr

Publications

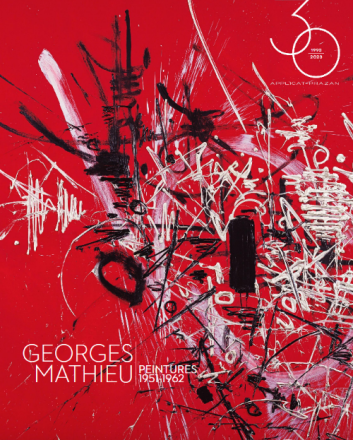

GEORGES MATHIEU

PEINTURES 1951 - 1962

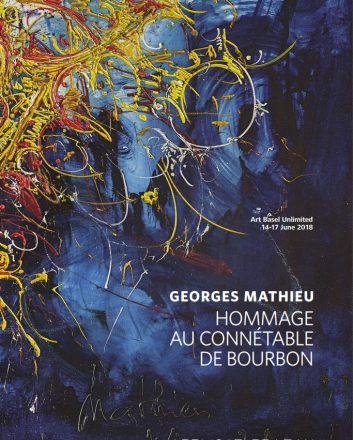

Hommage au Connétable de Bourbon

Georges Mathieu

Deux oeuvres du MoMA – Two works from MoMA

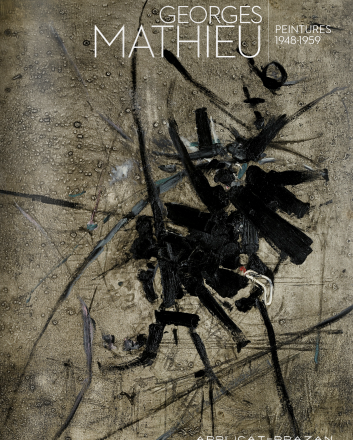

Jean Dubuffet - Georges Mathieu

Peintures 1948-1959

Georges Mathieu

les artistes

- Karel Appel

- Jean-Michel Atlan

- Martin Barré

- Jean-René Bazaine

- Roger Bissière

- Victor Brauner

- Camille Bryen

- Serge Charchoune

- Corneille

- Olivier Debré

- Jean Dubuffet

- Maurice Estève

- Jean Fautrier

- Otto Freundlich

- Roger-Edgar GILLET

- Hans Hartung

- Jean Hélion

- Auguste Herbin

- Asger Jorn

- Wifredo Lam

- André Lanskoy

- Alberto Magnelli

- Alfred Manessier

- André Masson

- Georges Mathieu

- Serge Poliakoff

- Jean-Paul Riopelle

- Gérard Schneider

- Pierre Soulages

- Nicolas de Staël

- Victor Vasarely

- Bram van Velde

- Geer van Velde

- Maria Elena Vieira da Silva

- Otto Wols

- Zao Wou-ki