Hans Hartung

1904 - 1989

Hartung was a major figure of Abstraction and one of the pioneers of abstract art, acknowledged as the ‘father of tachism’. An originator of Gestural Abstraction, Hartung only really became known after 1945.

Hartung was born into a family of doctors and amateur musicians, from whom he inherited a particularly developed musical sensitivity that encompassed both baroque and dodecaphonic music, and which in a sense served as a constant echo to his painting.

His early vocation was placed under the manifestation of instinct, speed and the mark. Natural elements presided over the elaboration of his future work’s plastic vocabulary rooted in his intense feeling for introspection. He later confided: “Painting has always meant for me the existence of reality, a reality embodied by resistance, fervour, rhythm and pressure, but which only exists for me if I capture it, define it, immobilise it for a moment that I would like to last for ever” (Autoportrait, Monique Lefèbvre, Grasset, 1976). His desire to draw began when, aged six, he was frightened by a storm. He described a flash of lightning, a clap of thunder and the storm’s violence: “I caught the flashes of lightening as they appeared in one of my school notebooks. I had to finish drawing their zigzagging on the page before the thunder burst. Like this I managed to ward off the thunder. Nothing would happen to me if my line could follow the speed of the lightening. These flashes of lightening enabled me to understand the speed of the line, the desire to capture, in pencil or brush, the moment and they made me understand the urgent nature of spontaneity” (op. cit

“ Painting has always meant for me the existence of reality, a reality embodied by resistance, fervour, rhythm and pressure, but which only exists for me if I capture it, define it, immobilise it for a moment that I would like to last for ever. ”

This passion for drawing never left him. In the schools attended by the nobility and upper classes in Basel, Leipzig and Dresden (1921–1924, baccalaureate in Latin and ancient Greek), his masters observed: “You are again making your horrible ink stains to form the subject… In drawing after drawing, I had succeeded in no longer figuring anything” (op. cit.). He made completely abstract portraits of his school friends in which they were able to recognise themselves through the lines and rhythms. He was also fascinated by astronomy and photography, anticipating his future plastic concerns. He made his own telescope with a camera attached to it. He observed fragments of reality despite their abstract appearance. Through photography, which he practised throughout his life, he was able to capture the ephemeral, portions of reality visible to the eye (the first major exhibition of Hartung’s photographs was held at the Centre Noroit in Arras in 1976). Attracted by nature and religion, he considered becoming a minister. However, the call of art was stronger. He saw the work of Rembrandt for the first time and was profoundly affected. “Looking at the folds of the mother’s dress (The Family) I discovered that Rembrandt also made stains, stains that have their own existence, rhythm, colours and expressiveness. I knew then that I would become an artist” (op. cit.).

Hartung also studied Goya, Hals, El Greco and, in 1921 and 1922, the German Expressionists such as Nolde and Kokoschka, who deformed appearance in order to achieve pure expression. The image gradually fades, replaced by stains and tension. The subject is already of little importance. Unaware of the work of the great artists of the previous generation (Picasso, Braque, the Delaunays, Kandinsky and Klee), Hartung’s first abstract watercolours, painted in 1922, cannot be compared to anything that had been done before. With complete spontaneity, the young artist marvels at the symbolic language of his lines, inks and colours. He subsequently continued to use colour in a structured manner employed as a dynamic factor. These watercolours were shown as reproductions in an album published in 1966 with an introduction by Will Grohmann. They were followed in 1923 and 1924 by a series of charcoal and red chalk drawings, in which speed of execution is already the decisive factor.

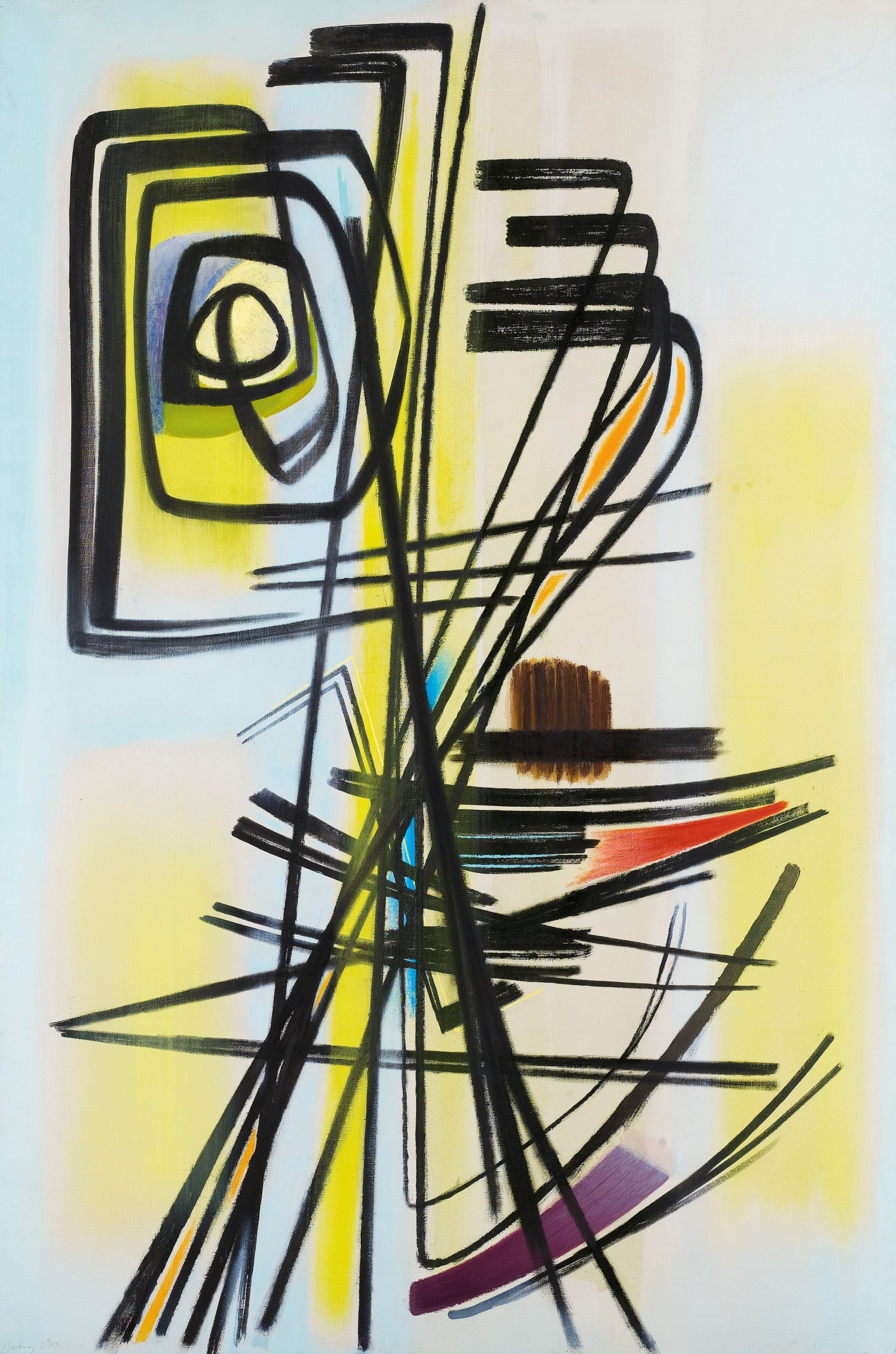

Oil on canvas

146 x 97 cm

Oil on canvas

146 x 97 cm

In 1924 Hartung began to study philosophy and art history at the Beaux-Arts in Leipzig. In 1925 he met Kandinsky at a lecture given by the latter, and discovered another form of abstraction, although he remained critical about Kandinsky’s research, which was opposed to geometrism and was equally innovative. He turned away from the Bauhaus, refusing the avant-garde work of Mondrian, over whom he preferred the Beaux-Arts of Dresden (1925–1926) and Munich (1928), where he continued to study classical tradition and techniques (his only figurative works, later destroyed during a bombing). In 1926 Hartung received a fresh shock upon discovering modern painting as it was practised beyond Germany’s frontiers, during a visit to the International Exhibition in Dresden: impressionism, fauvism and cubism. He was particularly interested by the work of Matisse, Braque, Picasso and Rouault. He continued to make numerous copies of the works of the masters in museums and from reproductions. In the summer he went on a bicycle tour of Italy. He decided to visit Paris, arriving in October 1926 and remaining in the city until 1931. This stay was interrupted by several journeys (to Barcarès near Perpignan in 1927, and to Holland and Belgium). He studied the works of Cézanne, Van Gogh and the cubists, who were an influence on his work until 1932. He considered the relationship between aesthetics and mathematics (distances, proportions, rhythms). He ignored the ‘free academies’ and visited museums and exhibitions. Extremely solitary, he had no contact with other artists. His meeting with a young Norwegian woman, Anna-Eva Bergman, broke this isolation. In September 1929, five months after first meeting, they were married.

The first exhibition of Hartung’s works took place in November 1931 at the Kühl Gallery in Dresden, and was followed the year after by an exhibition with his wife at the Blomqvist Gallery in Oslo. During this period the couple lived on an island in the south of Norway. He was deeply affected by the death of his father in 1932 and, faced with the rise of Nazism, left Germany to take refuge in the Balearic Islands. Passing through Paris, he left a few works with Jeanne Bucher. He built himself a small house near Fornells, a fishing port on Minorca, where he and his wife spent 1933 and 1934, a period that was to be highly productive.

Abandoning cubism, Hartung now returned to the spontaneous experimentation of his early years. He did not give these works a title, simply dating them, after the letter T, or more rarely G, so that we are able to place them in chronological order. As his assets had been blocked in Germany, he travelled to Berlin to try and arrange his financial affairs. He continued to push his work to its utmost limits, and both artist and work became identified in a total quest. In 1935, refusing to comply with the rules for art dictated by Nazi political propaganda, he fled from Berlin and its police with the help of Will Grohmann and Christian Zervos. Hartung now settled permanently in Paris, finding a studio at number 19 rue Daguerre. He became friends with Jean Hélion and Henri Goetz, and also met Mondrian, Kandinsky, Magnelli, Domela, Miró and Calder, with whom he exhibited at the Galerie Pierre. Up until the war, he took part in the Salon des Surindépendants. Between 1934 and 1938 he painted several series, titled Taches d’encre. All the characteristics of his mature style are already present here: contrasting masses and lines and stains and hatching, supported by a technical control in which improvisation remains ‘on probation’. It was this disconcerting style with its complete freedom, at the time entirely new to the abstract movement, which years after the war made him famous. Further financial difficulties forced him, however, to move into a smaller studio at number 8 rue François Mouthon. A difficult period commenced, during which he drew on paper tablecloths in bistrots. His wife fell seriously ill; they divorced, and Anna-Eva returned to Norway. Housed for a year by Henri Goetz, Hartung worked in the studio of his friend the sculptor Julio Gonzalez, and himself began to sculpt.

An artist of exceptional stature, Hartung always remained true to his beliefs. In the political domain he continued his struggle against Nazism, enrolling on the list of volunteers against Hitlerism, and in late 1939 joining the French Foreign Legion. In July of that year he married Roberta Gonzalez and, on demobilisation, lived in the Lot with the sculptor’s family, although Julio Gonzalez himself died in March 1942. When the Germans occupied the Zone Libre (Free Zone), Hartung fled to Spain with the help of Picasso. In Spain he spent a while in Franco’s prisons, before once more joining the Foreign Legion. He was seriously wounded during the assault on Belfort and had to have a leg amputated. In 1952 he met his ex-wife Ann-Eva again, by chance, at a retrospective of Julio Gonzalez’s work at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. “It was the final day and crowded. Suddenly I recognised a familiar silhouette. I remained nailed to the spot, my heart beating wildly. Anna-Eva and I advanced towards each other” (op. cit.). The power of destiny… Hartung remained convinced that “a work of art is a parallel manifestation of the artist’s life, an externalization of the forces within him, of everything which comes into play to push him into action, of everything which involves his impulses, his tendencies and experiences” (op. cit.). Roberta Gonzalez stepped aside and Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman took a studio in rue Cels.

On his return to Paris at the end of 1945, Hartung began to paint again and also became a French citizen. This introduction concerning the period which precedes that studied in this book is justified by the continuity in an oeuvre that was already mature and in which Hartung continued to develop an innovative language, paradoxically to be overshadowed by the post-war Abstract generation. It should also be pointed out that, because of his intentional isolation, “Hartung’s work has practically no repercussion between 1921 and 1945” (Mathieu, De la révolte à la renaissance, Gallimard, 1973).

Despite an exhibition of his work in 1939 – the first to be held in the capital —with works by Roberta Gonzalez at the Galerie Henriette, art lovers attending the first Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in 1946 discovered an unknown artist. Hartung was not a frequent participant at this salon, preferring the Salon de Mai. He was in contact with Poliakoff, Schneider, Marie Raymond and Domela, showing his work with the latter in premises in rue Cujas. This sufficed for him to be noticed by a number of well-informed critics, such as Charles Estienne, Wilheim Uhde, Léon Degand and Madeleine Rousseau, who in 1949 published in Stuttgart the first book about the artist, with prefaces by James Johnson Sweeney and Ottomar Domnick.

It was equally Madeleine Rousseau who wrote the catalogue introduction to Hartung’s first solo exhibition, held in Paris in 1947 at a small gallery named after its owner, Lydia Conti, and which had opened for this event at number 1 rue d’Argenson. Thirteen paintings were shown, dating from 1935 to 1947. Charles Estienne remarked on their tragic ‘intensity’. Up until 1957 Hartung’s works possessed a rebellious character. From 1945 onwards the grey stains appear and, around 1947 and 1948, the strong supporting line signals a new direction. It should be mentioned that until the end of the 1950s Hartung would work simultaneously on drawings and paintings. To be more exact, he worked on sketches, pastels and preparatory drawings for the paintings. When he began the final painting, however, the line remained just as elegant. Although Hartung’s work sometimes presents a similarity to ideograms, the artist always denied having been influenced in any way by oriental calligraphy. His line is indeed more emphatic and does not share the ideogram’s decorative character.

In 1948 Hartung had a second exhibition in Lydia Conti’s gallery, showing drawings produced between 1922 and 1948. Alain Resnais directed a film about the artist, which he showed in Germany and at the Galerie La Hune in Paris in 1950.

A number of group exhibitions during the period revealed this totally new form of painting. These were heroic years for abstract art, whose practitioners were shown in the new galleries. In December 1947 an exhibition was organised by Georges Mathieu at the Galerie du Luxembourg in rue Gay-Lussac, which Eva Philippe had opened the previous year. Under the title L’Imaginaire the artist presented works by Hartung, Atlan, Wols, Bryen, Arp, Riopelle, Ubac, Vulliamy, Brauner and Solier, with a text by Jean-José Marchand. This was followed in April 1948 by a second exhibition organised by Mathieu, this time at the Galerie Colette Allendy, which was given the enigmatic title HWPSMTB, the initials of each participant’s name: Hartung, Wols, Picabia, Stahly, Mathieu, Tapié and Bryen. A catalogue was produced with texts by each contributor, except for Hartung and Stahly. Jean-José Marchand wrote: “Humour and tragedy combine here to strengthen (in appearance) old doctrines and produce (in fact) an entirely new art, which constitutes our original post-war contribution” (Paru, June 1948).

Colette Allendy showed Hartung’s work again in group exhibitions in 1949, and in 1950 with D’une saison l’autre, along with a text by Charles Estienne, and which also included works by Schneider and Soulages and the young artists Doucet and Gauthier.

In July 1948 a further exhibition was held at the Galerie des Deux-Isles, a new gallery run by Florence Bank. Mathieu showed beside his own work that of Hartung, Wols, Tapié, Picabia, Ubac, Arp and Germain, with drawings, prints and black-and-white lithographs under the title White and Black. There were catalogue introductions by Michel Tapié and Édouard Jaguer, who wrote: “For all those who are present here, the key lies in the conquest of a subconscious but real place,” and “A new phenomenon whose meteoric passage also illuminates writing.” That November, at the Galerie du Montparnasse, a former bookshop that had been transformed into a gallery and which was run by Gilberte Sollacaro, the first confrontation with American painting took place: Bryen, Hartung, Mathieu, Picabia and Wols were hung next to de Kooning, Gorky, Pollock, Renhardt, Rothko, Russel, Sauer and Tobey. Ultimately, in 1957, at Nina Dausset’s gallery, which had opened two years earlier in rue du Dragon, Mathieu showed alongside his own work and under the title Véhémences confrontées a group of international artists: Bryen, Capogrossi, de Kooning, Hartung, Riopelle, Russel and Wols. A text was written by Michel Tapié. In the same year, Hartung participated in the exhibition Advancing French Art in New York, Chicago, Baltimore and San Francisco. There were also group exhibitions organised by Denise René who, in 1944, had opened a gallery at number 124 rue La Boétie. Hartung was included from 1946 onwards, with Schneider, Deyrolle, Dewasne and Marie Raymond (text by R. de Solier). These exhibitions continued in 1947 and 1948 with Tendances de l’Art abstrait and in 1949 with Quelques aspects de la peinture présente. We should also mention his participation in 1952 in Un art autre at the Galerie Facchetti, which took the title of a work by Michel Tapié published on the same occasion, and the exhibition organised by Charles Estienne in the hall of the Théâtre de Babylone titled Peintres de la Nouvelle École de Paris; in 1954 in the group exhibition Divergences organised by R.V. Gindertaël at the Galerie Arnaud; and in Individualités d’aujourd’hui at the Galerie Rive Droite. From 1954 until 1958 he was invited to participate in l’École de Paris at the Galerie Charpentier.

These group events were important as they enabled critics and the public to follow Hartung’s progress, particularly since solo exhibitions of the artist’s recent work were infrequent.

The first of these solo exhibitions was held in November 1956 at the Galerie de France and attracted a great deal of interest. Following the signing of a contract with Gildo Caputo, the gallery’s director, he showed pastels in 1958; paintings from 1922 to 1939 in 1961 (catalogue); recent works in 1962 (catalogue); and 15 paintings done in 1963 and 1964 in1964.

These exhibitions were followed by exhibitions of recent paintings in 1966, 1969, 1971, 1972, 1974 and 1979. In 1977, the gallery showed 25 works from 1922 to 1952.

From 1985 onwards, Hartung’s work was shown by the Galerie Daniel Gervis.

His work also began to be shown in a growing number of galleries and museums in the provinces and abroad.

Among the most significant of these were: in 1957, a travelling retrospective exhibition in Germany. In 1959, a retrospective at the Musée d’Antibes (his first exhibition in a French museum). In 1960, the Venice Biennial, at which he was awarded the Grand International Prize for Painting, with a room in the French pavilion devoted to his work. In 1963 and 1964, a travelling retrospective exhibition in Zurich, Vienna, Dusseldorf, Brussels and Amsterdam. The complete list of these exhibitions is to be found in the catalogue published by the Galerie Marwan Hoss, Paris, for the presentation in 1990 at the Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporaine (FIAC) of Hartung’s last works.

He was invited to the first Documenta in Kassel in 1955.

Between 1952 and 1954 Hartung began to develop a new pictorial language. He had abandoned the tachism of the years 1934 to 1938, replacing colour by line – counterpoint of the line against the background, with the addition of the stain-form producing a highly personal style of spatial dynamism – before introducing more complex forms characterised by curves, crescents and bundles of thick black bars executed with rapid fluid brush strokes against a neutral background, the sole counterpoint. This gestural dynamism then subsided to be replaced by a less spontaneous form of composition. Then, between 1955 and 1959, without renouncing one of the principal characteristics of his work, the antagonism between forms and signs and plain backgrounds, the rhythm of the lines becomes more intense, suggesting clumps or bundles. The lines become tenser and adopt different thicknesses, an evolution also apparent in his graphic work, which in his opinion was as significant as the paintings.

A first exhibition of his etchings was held in 1954 at the Galerie La Hune which, in 1958, also presented his lithographs.

In 1956 the Galerie Craven showed drawings made between 1921 and 1938.

In 1955, Hartung was invited to the Biennial of Graphic Arts at Ljubljana, at which he also showed his work on several subsequent occasions up until 1965, being awarded the Prize of Honour in 1967 at the 7th Biennial. Three series of prints stand out: 1946 to 1947; winter 1952 to 1953, done while he was participating for the first time with his paintings at the Venice Biennial; and 1957 prints and lithographs, with a series of pastels continued until 1961 (he hardly painted in the years 1959 and 1960). In 1963 he began a new series of lithographs made at Saint-Gall. In 1964 Hartung-Bergman, a travelling exhibition of prints and lithographs, was shown in Israel. In 1965, for the publication of the catalogue raisonné of his prints (1921–1965) by the Galerie Rolf Schmücking in Braunschweig, an exhibition of Hartung’s entire graphic oeuvre was shown at the town’s museum.

Reprinted, Basel, 1990.

From 1961 onwards a new period began, characterised by scrapings in the still-wet-paint, which allowed the canvas to show through. Appearance of interlacings, extremely delicate undulations tangled to give the illusion of bars, scratchings and streaks. The lines gradually disappear, replaced by dark masses, like threatening smoke, without any graphic character, whose tones are superimposed against a lighter background, on huge canvases.

Hartung’s work becomes stripped of any reference to the exterior world or anything that might reflect a state of mind. “We enter,” Hartung tell us, “the unknown, a zone that has yet to be created… internal movements can be a basis, just an incitement.” In 1969 colours reappear, with a preference for lemon yellows, intense blues, brick reds, light greens and the ever-present black, lending expression to a poetic inspiration that commands the gesture.

In 1972 he moved with Anna-Eva Bergman into a large villa-studio above the town of Antibes, arranged to suit their needs. In 1959 he had already had a studio altered according to his plans near the Parc Montsouris. His wife died in the Antibes villa in 1987, and he himself died there on 14 December 1989.

Action painting is rooted in the work of Hartung, who had paid a first visit to the USA in 1964, although his works had been shown there since 1957.

A large number of retrospectives with catalogues were held from 1965 onwards.

1966 Museo Civico di Torino.

1969 Musée National d’Art Moderne de Paris, followed by Houston, Musée du Québec, Montreal.

1974 Wallraf Richartz Museum, Cologne.

1975 National Gallery, Berlinand Stadtische Gallery, Munich.

1977–1981 Travelling exhibition of lithographs and prints organised by the Centre Georges Pompidou.

1980 Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris: works from 1922 to 1939, text by André Berne-Joffroy. Musée de la Poste Paris: tapestries and woodcuts by Hartung and his wife.

1981 Stadtische Kunsthalle, Dusseldorf and Staatsgalerie Moderner Kunst, Munich. Henie-Onstad Foundation, Norway.

1986 Musée d’Evreux. Text by Pierre Daix. Biography and bibliography.

1987 Premières peintures 1922–1949. Musée Picasso, Antibes.

1991–1992 Hartung oeuvres extremes, 1922–1989. Montbéliard and Ludwigsburg Museums. Catalogue.

2019-2020 Hans Hartung La fabrique du geste. Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris. Catalogue.

Hartung achieved international recognition and was given many awards: 1970, Grand Prix des Arts de la Ville de Paris; 1977 member of the Institut Académie des Beaux-Arts, Paris, among other distinctions. He continued to work far from the intriguing tumult of the capital. Universal, never referring to nature but drawing from it its energy, his work born from a profound asceticism goes beyond the visible to deliver a message of great sensitivity with an economy of matter and precise gestures. He had a decisive influence on the following generation.

Hartung’s works are preserved in many museum collections. In Germany, besides Berlin, Bonn, Cologne, Hamburg, the Hartung rooms at Darmstadt (1984) and Munich (1982); the United Kingdom, Australia, Austria, Brazil, the USA, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Norway, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, Yugoslavia, and in France: Musée d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou and Ville de Paris, Aix-en-Provence, Antibes, Chalon-sur-Saône, Dunkerque, Grenoble, Lille, Lyons, Marseille, Nantes, Rouen, Fondation Maeght St Paul, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Strasbourg and Toulouse.

- Van Gindertaël: Hans Hartung, Tisné, I960.

- Dominique Aubier: Hans Hartung, Le Musée de Poche, Fall, 1961.

- Jean Tardieu: Hans Hartung, Hazan, 1962.

- Special issue Cimaise, 1974, for the artist’s 70th birthday.

- Pierre Descargues: Hans Hartung, Cercle d’Art, 1977.

- Michel Ragon: Vingt-cinq ans d’Art vivant, Galilée, 1986.

- Pierre Daix: Hans Hartung, Bordas/Daniel Gervis, Paris, 1991.

Excerpt from L’École de Paris 1945–1965: Dictionnaire des peintres

Ides et Calendes Editions, courtesy of Lydia Harambourg

www.idesetcalendes.com

les artistes

- Karel Appel

- Jean-Michel Atlan

- Martin Barré

- Jean-René Bazaine

- Roger Bissière

- Victor Brauner

- Camille Bryen

- Serge Charchoune

- Corneille

- Olivier Debré

- Jean Dubuffet

- Maurice Estève

- Jean Fautrier

- Otto Freundlich

- Roger-Edgar GILLET

- Hans Hartung

- Jean Hélion

- Auguste Herbin

- Asger Jorn

- Wifredo Lam

- André Lanskoy

- Alberto Magnelli

- Alfred Manessier

- André Masson

- Georges Mathieu

- Serge Poliakoff

- Jean-Paul Riopelle

- Gérard Schneider

- Pierre Soulages

- Nicolas de Staël

- Victor Vasarely

- Bram van Velde

- Geer van Velde

- Maria Elena Vieira da Silva

- Otto Wols

- Zao Wou-ki