Jean Dubuffet

1901 - 1985

A painter, lithographer, sculptor, musician, writer and poet, Dubuffet also wrote the most significant texts about his work. One example of these is the comments on his processes in his Notes, published as an appendix to Georges Limbour’s book Tableau bon levain (pp. 91–97, Drouin, Paris, 1953) and in Mémoire sur le développement de mes travaux à partir de 1952, a text which figures in the catalogue to his retrospective exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (pp. 131–199, 1960). Dubuffet never ceased to shake up the established order in art, substituting derision and the unexpected for traditional values. He created an enormous body of work that stands apart from other alienating currents. For a long time his works were considered as expressions of outrage directed at reason and culture. A corollary of his work was his militancy for an art of exception, that of the mentally ill, the simple of mind and children, to which he gave the name ‘art brut’ (raw art). Becoming in this context a collector, he organised between 1947 and 1951 several events in the basement of the Galerie Drouin. In 1949, during one of these presentations of art brut, he wrote in L’Art brut préféré aux arts culturels: “Real art is always where you do not expect it to be, where nobody is thinking of it or pronouncing its name. Art hates being recognised and greeted by its name.” He founded a museum to house his collection at number 17 rue de l’Université, transferring the contents to number 137 rue de Sèvres in 1962. Since 1971 the Compagnie de l’Art brut has been located in Lausanne. In 1959, Alphonse Chave held an exhibition titled L’Art brut in his Galerie des Mages in Vence, presented by Dubuffet, and in 1967 the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in turn organised an exhibition of the artist’s work.

“ It is true that the manner of drawing in the paintings shown is entirely free of any conventional know-how of the sort that we are used to seeing in paintings done by professional painters and there is no need for any special studies or particular gifts to execute similar works. ”

Dubuffet always set himself the highest standards for his work. A man who appreciated debate, he kept up a continual controversy, which still rumbles on today. His immense output, varied, rich and experimental, remains the work of a unique inventor of forms, with a preference for irreverence and fantasy. In 1954 Alfred Barr wrote: “It is possible that the most original painter to have come out of Paris since the war is not an abstract painter. A man of exceptional intelligence and maturity, Jean Dubuffet combines a childish style with daring innovations in his manner of painting and a grotesque sense of humour” (Les Maîtres de l’Art moderne). Because of the extent of the writings which exist about Dubuffet and his work, beginning with his own texts, we will only mention the most important documents that refer to the period in question here, and it is suggested that the reader consult the bibliography in the catalogue of the Donation Dubuffet to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, published in 1967. In addition, considering the abundance of his work, we will only evoke the period that comes within the scope of this book. Born into a family of wine merchants, at the lycée one of his fellow pupils was Georges Limbour, who was to become his first critic, and another, Armand Salacrou. In 1916 Dubuffet enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts at Le Havre. In 1918 he left for Paris to study painting at the Académie Julian. Here he met Suzanne Valadon, Elie Lascaux and Max Jacob, and painted in a traditional style that tended towards the academic. In 1924 he gave up painting and left for Buenos Aires. On his return to France, he took over the responsibility for the family wine business, before founding his own business at Bercy in 1930. In 1933 he decided to take up his brushes again and placed his business under management. He began to sculpt puppets. In 1937 he abandoned art for a second time until in 1942 he finally decided to devote himself exclusively and lastingly to painting, selling his wine business in 1947. He married Emilie Carlu, known as ‘Lili’. From the start, his work presented a succession of ‘cycles’ that corresponded to chronological phases (which did not exclude however a return to certain subjects). To avoid confusion, we will follow this listing of periods that Dubuffet always commented in his theoretical writings.

1942 to April 1945, Personnages; Métro; Vues de Paris. Paysages; Jazz; Murs; Messages, close to children’s drawings.

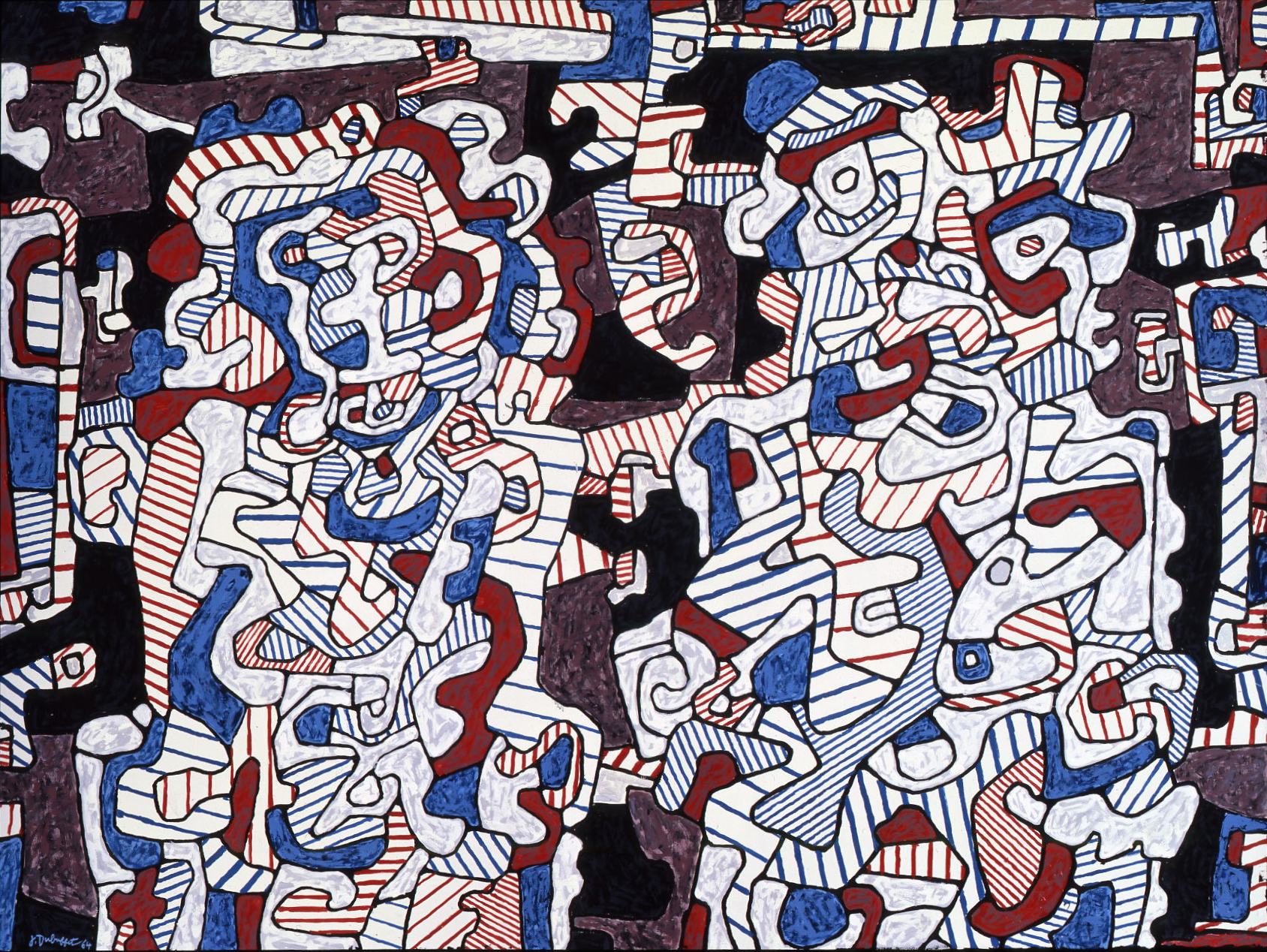

Vinyl on canvas

150 x 200 cm

Oil on canvas

116 x 89 cm

Dubuffet rented a studio at 114 bis rue de Vaugirard. He became friends with Jean Paulhan, who introduced him to René Drouin. In 1944 the latter organised Dubuffet’s first exhibition in his gallery in Place Vendôme, with a catalogue introduction by the writer. The critics were unsettled by these works, with their deformed shapes and bright colours. This mechanism of provocation was never to stop, and the artist explained this process nearly 25 years later in his manifesto Asphyxiante Culture (J.J. Pauvert, Paris, 1968): “There is a single climate healthy for the creation of art: that of permanent revolution.” Although Picasso defended his works, Dubuffet himself referred to them during this period as ‘unmentionables’.

May 1945 to July 1946, Mirobolus Macadam et Cie; Hautes Pâtes.

In 1946 a new exhibition was held at the Galerie Drouin entitled Mirobolus Macadam et Cie, accompanied by a book by Michel Tapié with the same title and ‘descriptive indications’ by the artist, to which was added a manifesto, Prospectus aux amateurs de tout genre (Coll. Métamorphose XXI, Gallimard), in which he refuted the purpose of museums and art dealers and declared: “It is true that the manner of drawing in the paintings shown is entirely free of any conventional know-how of the sort that we are used to seeing in paintings done by professional painters and there is no need for any special studies or particular gifts to execute similar works.” To make these dark works, executed in thick impasto, he replaced oil paint by a mixture of ceruse and whiting, liquid mastic, asphalt, tar, sand and gravel, shop display varnish and waste. His dirty colours were surprisingly similar to the different shades of walls or ground. Dubuffet, abandoning traditional instruments, drew his graffiti with scrapers, spoons or even his fingers. Grotesque grimacing characters stand out from this high relief.

Early in 1947, after arguing with everybody, he left for El Golea in the Sahara, to which he returned twice in the following two years. He brought back with him a profusion of drawings and gouaches presented in the collection Rosés d’Allah et clown du désert.

In October 1947 his Portraits were shown at the Galerie Drouin, with a text in his own hand, Causette: les gens sont bien plus beaux qu’ils croient, vive leur vraie figure. The exhibition was a series of likenesses of his friends or of personalities: Ponge, Paulhan, Léautaud, Limbour, Michaux, Fautrier, Antonin Artaud, Michel Tapié, Charles Ratton. “Those who have spoken, on the subject of my portraits, about an attempt at psychological penetration, have not understood anything at all; these portraits were anti-psychological, anti-individualistic, nourished by the idea that if you want to paint what is important you do not have to pay much attention, even in a portrait, to futile accidents…!!! It seemed to me that by depersonalising my models, and approaching them from the very general perspective of the human figure, I helped to release, for the user of my painting, different mechanisms of imagination or interest which would greatly increase the power of the likeness” (Files 10 and 11, Collège de Pataphysique. Documentation published by Noël Arnaud.) Faced by scandal, he was defended by Pierre Seghers, Paul Eluard and Marcel Arland. In 1946, Charles Estienne wrote about his painting.

Dubuffet was introduced to the United States by Clément Greenberg, and in 1951 his work was exhibited in New York at Pierre Matisse’s gallery. Pierre Matisse remained his dealer from 1945 to 1960.

From May 1949 to January 1950 Dubuffet worked on Paysages grotesques, shown at the Galerie Drouin in 1949. At the end of the year he executed the illustrations for Métromanie and the lithographs for Anvouaiaje. From January 1950 to March 1951 he worked on Intermède; Corps de Dames. This led to a new scandal generated by the body of a sexually assaulted woman hurriedly incised in thick paste. “In the 40 or 50 paintings which I painted between April 1950 and February 1951 under the title ‘Corps de Dames’, the drawing should not be taken too literally. The always outrageously coarse and slovenly appearance, in which the figure of the nude woman is trapped, would, if taken at face value, imply abominably obese and deformed people. My intention was that the drawing should not give the figure any defined form… Equally the result of this same impulsion are the connections, apparently illogical, which we find in these nudes, of textures that evoke human skin (which sometimes even seem to assault our perception of decency, but this also seems to me effective) with other textures which have nothing to do with humans… In the same category may be included the apparent faults, that I seem inclined (too much so, no doubt) to leave in the paintings, for instance the involuntary stains, crass blunders, forms which are obviously false, anti-real, out-of-place colours, inappropriate, all things that must probably appear unbearable… But this is a feeling of unease that I am happy to keep up, as in fact it makes the painter’s hand very present in the painting, and prevents objectivity from getting the upper hand” (op. cit.).

Among these women’s bodies appears the Géologue, which from March 1951 to October 1951 introduced a new cycle, painted in Paris. Sols et Terrains, Paysages mentaux, at the same time as Tables paysagées and Pierres philosophiques. Monochrome paintings in which the pictorial matter comprises plaster, glue, plastic paints and mastic. Dubuffet commented: “I like, for these landscapes, to interfere with the scale, so that it is not sure whether the painting represents a vast expanse of mountains or a tiny plot of land. [Some] are purely physical; they evoke places, soils, sub-soils sometimes, in a very real manner that avoids any mental rambling… But the matter then sometimes becomes more complicated… The numerous experimentations that I conducted for these paintings sometimes resulted in strange apparitions, where the false becomes confused with the real, and the landscape adopts an absurd appearance evoking, rather than a real place or real natural matter, a form of aborted or incomplete creation… The extremely concrete became confused in the painting with the completely absurd, many forms adopting an ambiguous character. They can indeed strike the person looking at the painting, either as representing uneven ground, or as living people (living a singular life, halfway between existence and non-existence, between the real and the imaginary, halfway between belonging to the places objectively represented in the painting and the artist’s mental world” (op. cit.). These works prefigure the Texturologies (1958) and Matériologies (1960).

From November 1951 to April 1952, Dubuffet made his first visit to New York. He continued Sols et Terrains and worked on Bowery Bums. An exhibition was held at the Galerie Pierre Matisse in early 1952.

On his return to France, he began a series of drawings in ink. Terres Radieuses are austere and similar in appearance to the preceding paintings. “I took pleasure in creating effects obtained through a subtle combination of the real and the absurd.” The series were shown at the Galerie La Hune at the end of 1953.

From October 1952 to March 1953 he worked on the series Lieux momentanés. These were lacquered paintings on canvas, without relief, in which he returned to using bright colours. From 1953 to 1957, he worked on the series Assemblages d’empreintes and, in 1955, he begun Tableaux d’assemblages, starting with Petits tableaux d’ailes de papillons, based on previous experiences.

In 1954 Dubuffet showed at the Galerie Rive Gauche Petites statues de la vie précaire, which continued some of the processes begun in Assemblages d’empreintes, works prepared using natural elements and waste. During the summer, his wife took a cure in the Puy-de-Dôme. The couple moved to the country and Dubuffet began a series of Vaches in thick impasto, using bright colours and obtaining a grotesque appearance.

In 1954 a retrospective exhibition was held at the Cercle Volney in Paris. Early in 1955 there was an installation at Vence. From 1956 to 1960, Dubuffet worked with the surfaces he walked on, floors and ground. He transcribed an entire landscape of impoverished vegetation, rendered in a playful poetic style, with a base of mud and clinker in shades of browns, greys and blacks.

In 1957 the catalogue of the exhibition Tableaux d’assemblages at the Rive Droite Gallery was written by Georges Limbour, with a postscript. “I have always liked, it is a form of vice, to employ only the most common materials… I like to proclaim that my art is an enterprise of rehabilitation for disparaged values” (op. cit.).

A further exhibition was held in 1960 at the Kunsthaus in Zurich. In the spring of that year he began the Lieux cursifs, which have a very thick texture applied with a knife and in which the subjects (figures and houses) are cut into the matter with its tones of white, bistre and ochre. Between September and December 1957 he worked on Topographies; Portes; Tables; Sols nus; and Texturologies. In 1958 he worked on paintings that assembled lithographs in a private studio at number 149 rue de Rennes.

The collages Déclencheurs d’imagination are a turning point before the series Texturologies (1958–1959), which was shown in 1959 at the Galerie Daniel Cordier, rue Duras, under the title Célébration du sol, accompanied by a text, Texturologies Topographies, which had already appeared in Les Lettres nouvelles no. 8, Paris, 22 April 1958: “Note that my preference is not for picturesque ground, luxuriously furrowed or historiated… I want to make it clear that my paintings show ground seen from above, with a vertical perspective… That the strips of ground evoked have the dimensions of a napkin or rather of a bed… increases my turmoil, through the dizziness generated by the equivocal nature of the dimension.”

Early 1959 Empreintes texturologiques, produced with black oil paint on paper, presented a tangle of crisscrossing lines. This was followed by the series Assemblages d’empreintes, drawn in Indian ink on the theme of Barbes and exhibited at the Galerie Daniel Cordier under the title As-tu cueilli la fleur de barbe. Complex lines invade all his works. At the same time he also worked on the series Eléments botaniques and Petites Statues, in coloured papier-mâché highlighted with ink, which led to the cycle Matériologies (late 1959 to early 1961). Works made with painted creased tinfoil, stuck to hardboard panels, or papier-mâché stuck to hardboard or placed on a wire mesh stretched over a frame. Vinyl pastes, polyester resins, tree barks, sand and mica dust were added to the surface and then painted over. In 1960 he moved into his new house in Vence, ‘Le Vortex’, and produced the series of drawings titled Aires et Sites.

In 1960 there was a retrospective of his drawings at the Galerie Berggruen in Paris. In 1961 he painted the series Paris-Circus, in which he returned to his subjects of 1943 to 1944; although this time he abandoned working-class Paris, he represents a frenzied world where a thick crowd fills the maze of shopping streets. The series was shown at the Galerie Daniel Cordier in 1962. Series Baladins and Légendes. In 1962 he spent the summer at the house he had recently bought at Le Touquet. He began work on L’Hourloupe, and was to work on this series until 1964. “It is the unreal that delights me now; I have an appetite for non-truth, false life, the anti-world; my works are embarked on the path of the unreal. I feel that realism and unreality are the two poles between which art is divided, much more than the two foolish notions of abstract and figurative employed today by all simple minds [to obtain] effects that are really violent and effective” (op.cit.). In these imprecise compositions, agitated shapes move in a proliferation of cells with blues, reds, whites and blacks drawn in biro. This extravagant visionary world soon spreads to all the objects which surround us and, with Personnages en marche, gives a rough ride to our instinct for rationalism.

In June and July 1964 L’Hourloupe was shown at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice (55 paintings and 52 gouaches and drawings), with catalogue texts by Renato Barilli and Paolo Marinotti.

Then in December 1964 and January 1965 he showed in Paris at the Galerie Jeanne Bucher (18 paintings) and at the Galerie Claude Bernard (46 gouaches), Foire aux mirages with a personal catalogue preface by Hubert Damisch.

Lastly, in 1966 he showed at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Early in 1966 he began a long and important series of sculptures in expanded polystyrene painted in vinyl. In 1967 he built his Cabinet Idéologique.

In 1956 Daniel Cordier began showing Dubuffet’s works. He opened his gallery with a group exhibition of Dewasne, Dubuffet and Matta, with texts by the artists. From 1960 onwards Cordier became Dubuffet’s dealer for Europe and the United States, an exclusivity which ceased in 1963 (Donation Daniel Cordier Le regard d’un donateur, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, exhibition 1989. Catalogue).

In 1957, Dubuffet exhibited with Michaux and Wols at the Studio Facchetti, where he had already participated in group exhibitions, invited by Michel Tapié in 1951 for Signifiants de l’informel, and in 1952 for Peintures non abstraites and Un Art autre.

In 1958 there were solo exhibitions at the Arthur Tooth & Sons Gallery, London, with a catalogue introduction by the artist, and at the Galleria del Naviglio in Milan. From 1958 to 1959 and in 1961, he showed with the Galerie Daniel Cordier at Frankfurt.

Dubuffet’s first retrospective was held in the period 1960 to 1961 at the Paris Musée des Arts Décoratifs with 402 works shown. Catalogue with an introduction by Gaétan Picon and a text by Dubuffet, Apercevoir.

In 1961 a retrospective of his graphic work was held at the Silkeborg Museum (Denmark), with a catalogue raisonné prepared by Noël Arnaud. In 1962 a retrospective titled The Work of Jean Dubuffet (185 works) was presented in New York at the Museum of Modern Art, then in Chicago and Los Angeles. Catalogue by Peter Selz.

1963 Rétrospective, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nancy.

1964 exhibition of the series Phénomènes (324 lithographs from 1958 to 1962 and 14 paintings) at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice. Catalogue by L. Trucchi.

1966 Rétrospective , Tate Gallery, London; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Dallas, Catalogues.

1973 Jean Dubuffet, Grand Palais, Paris. Coucou Bazar – Petit journal. Dubuffet’s final works were shown at the Galerie Claude Bernard (1978) Théâtres de Mémoire, the Centre Georges Pompidou (1985), the École des Beaux-Arts (1985), and the Galerie Jeanne Bucher (1987) with the series Non-Lieux. Catalogues.

1985 Rétrospective Quarante années de peinture, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul-de-Vence. Catalogue by Jean-Louis Prat.

1988 Sols et Terrains 1956–1960, Galerie de France and Galerie Baudoin Lebon, Paris. Catalogue with an introduction by Daniel Cordier.

1990 Dubuffet. Des années 50 aux années 80, Gallery Urban, Paris. Catalogue (list of exhibitions and retrospectives.)

1967 Donation Dubuffet to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. Catalogue. His works are preserved in many museums in France and other countries.

- Jean Dubuffet: Prospectus et tous écrits suivants. The artist’s writings from 1944 to 1967, presented by H. Damisch in two volumes, Gallimard, 1967.

- Catalogue intégral des travaux de Jean Dubuffet, prepared by Max Loreau. 21 volumes. J.J. Pauvert, Paris, 1964–1968; Weber, Paris 1968–1971.

- Jean Dubuffet: no. 22, texts collected by Jacques Berne, L’Herne, Paris, 1973.

- Michel Ragon: Jean Dubuffet, G. Fall, Le Musée de Poche, 1958.

- Gaétan Picon: Le travail de Jean Dubuffet, Skira, Geneva, 1973 ; and Weber, 1973.

Excerpt from L’École de Paris 1945–1965: Dictionnaire des peintres

Ides et Calendes Editions, courtesy of Lydia Harambourg

www.idesetcalendes.com

Publication

Deux oeuvres du MoMA – Two works from MoMA

Jean Dubuffet - Georges Mathieu

les artistes

- Karel Appel

- Jean-Michel Atlan

- Martin Barré

- Jean-René Bazaine

- Roger Bissière

- Victor Brauner

- Camille Bryen

- Serge Charchoune

- Corneille

- Olivier Debré

- Jean Dubuffet

- Maurice Estève

- Jean Fautrier

- Otto Freundlich

- Roger-Edgar GILLET

- Hans Hartung

- Jean Hélion

- Auguste Herbin

- Asger Jorn

- Wifredo Lam

- André Lanskoy

- Alberto Magnelli

- Alfred Manessier

- André Masson

- Georges Mathieu

- Serge Poliakoff

- Jean-Paul Riopelle

- Gérard Schneider

- Pierre Soulages

- Nicolas de Staël

- Victor Vasarely

- Bram van Velde

- Geer van Velde

- Maria Elena Vieira da Silva

- Otto Wols

- Zao Wou-ki