Hélion’s first solo exhibition was given at the Galerie Pierre Loeb with Compositions orthogonales and Tensions courbes (1932), and the second took place in 1936 at the Galerie Cahiers d’Art. He paid regular visits to the United States, exhibiting there from 1933 and living between Paris and Virginia where, in 1935, he built a studio. As he travelled his circle of contacts began to widen, and he participated in numerous group exhibitions: at the Galerie Pierre, in Switzerland, London and the USA: Gorky, Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore, Kandinsky, Hartung, Picasso, Lipchitz. Fernandez, Magnelli, Gorin, Morris, Meyer Schapiro and Yves Tanguy, and also Henry Miller and André Breton.

In 1938 Hélion had another exhibition at the Galerie Pierre. The disbanding of Abstraction-Création had permitted Hélion to detach himself from the restricting codes of geometrics and neo-plastics. To avoid a dead end, he adopted a new structure introducing space and movement, suggesting an increasingly identical correspondence with reality: in this new arrangement of volumes and colours, he introduced Figures. This was the period of Grandes Figures abstraites (1937). He also made studies of trees from nature. In 1939 Hélion made his last abstract compositions (La figure tombée, priv. coll.), and also made a first attempt at a return to the identifiable with the series Têtes: Emile, Edouard, Charles, which led to his first major figurative composition Au cycliste (Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris), which marked his final abandonment of abstraction.

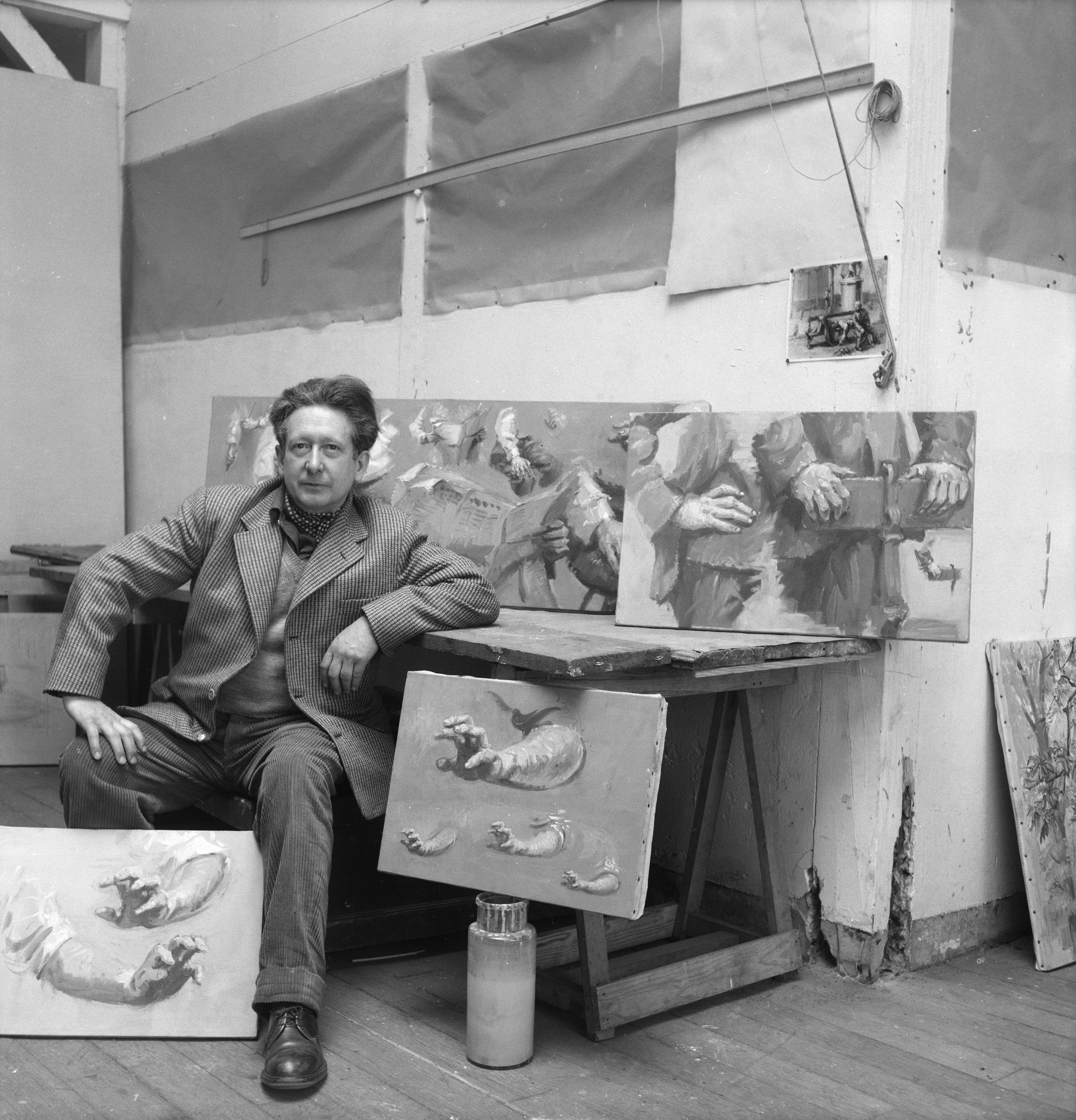

Called up in 1940, Hélion was taken prisoner and sent to a camp from which, in 1942, he succeeded in escaping. He managed to reach Marseille and met up there with Tzara, Duchamp, Brauner and Hérold, before obtaining a passage on a ship sailing for the United States. In New York Hélion found Mondrian, Calder, Max Ernst, Tanguy, Léger, Ozenfant and Breton. He painted the series Allumeurs, Fumeurs, and Filles aux cheveux jaunes, followed in 1945 by Figures de pluie. Les salueurs, Figures gothiques, Hommes assis. On his return to France in April 1946 he spent the summer at Cagnes-sur-Mer, where he worked on Figures demi-nues. That autumn he found a studio in Paris in rue Michelet, where he worked until the end of his life. In 1947 he painted A rebours (Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris), an important milestone in his work that summarises his painting since the abstract period: an approach to reality in which he perceived a mechanical dimension. The theme of nudes is combined with a person in an everyday scene, a theme that was to recur in the following years, with open fruit such as pumpkins in still lives.

An exhibition of Hélion’s recent work was held in 1947 at the Galerie Renou et Colle. His style became more realistic – nonetheless retaining a picturesque character – without seeking to be descriptive, something he had always rejected. This is how he defined Réalité in the ‘notes de travail’ which he kept throughout his career: “Any scene, however imaginary it may be, must coincide in some aspect (silhouette, colour, rhythm or whatever) with something ‘seen’. It must only include objects or persons which one day made an impression on me, separately or together. These objects or persons must be made with forms and colours that are part of a process” (1950, Carnets, donated by Hélion in 1979 to the Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris). He moved towards representing reality working from nature (Chrysanthèmes 1950, Grand Brabant 1958, Chou 1960), keeping as he says to the “seen” and the “lived”. “Real – Realism – Possible. Realism is the quest for Real through the appearance of what we meet, without changing anything: The window of the café of the Val-de-Grâce is like this, with this grandeur: appearance. Realism. But the man seated in it constitutes an archetype of ‘a seated man’. This is the passage from realism to real” (1966, op. cit.).

Between 1948 and 1950 Hélion painted a number of series that tended towards surrealism: Journaliers and Natures mortes à la citrouille, followed in 1949, after a visit to Italy, by female nudes, Journaleries, compositions that placed the nude in an everyday setting. This period came to a close in 1951 with Les Mannequineries. He contrasted the allegorical with the everyday in realistic compositions that differentiated him from the art scene of the time in which abstraction triumphed (Allégorie journalière 1951–1952, large charcoal on canvas, Fondation Christian et Yvonne Zervos, Vézelay). His subjects are derived from events observed or experienced. In 1952, in a second spacious studio on avenue de l’Observatoire, he painted a number of still lives with loaves, pumpkins and rabbits. He visited Spain to look at the works of Velasquez, Goya and El Greco. In 1953 he spent the summer on Belle-Île, where he bought a house, returning to Paris with a large number of landscape studies. In 1954 he executed a major composition of the Jardin du Luxembourg for which he had first made a large number of thumbnail sketches of strollers, benches and chairs, sweepers sweeping the dead leaves and statues. He completed this painting in the summer of 1955 on his return from a trip to Holland. This period marks a new phase in Hélion’s work in which he achieved a synthesis of image and sign. In 1956 he returned to the subject of Couples au parapluie and painted his first works on Belle-Île, where he spent the summer. From 1957 to 1958, in the studio at the top of the building in rue Michelet, he painted a series of interior scenes: portraits of his wife Pegeen sitting on a couch and a still life with a white soup ladle; Carmen; Toits; and Vanités, in which the innovate technique allows light to shine through the windows. In 1959 he began a series of portraits of friends, poets and collectors: Yves Bonnefoy, André du Bouchet, Jean-Pierre Burgart, Georges Bine and Pierre Bruguière (Musée Ingres, Montauban).

From 1960 to 1961 he returned to the theme of Luxembourg in the autumn, and also Toits with figures. He returned to Holland to look at the works of Hals and Rubens. In 1962 he bought a property at Bigeonnette, near Chartres, with a spacious studio in which he was able to paint large works, while also continuing to paint on Belle-Île and in his Paris studios. During these years he developed a form of gestural language that recalled the works of Magnasco he had seen in Venice and Genoa during his first visit to Italy in 1947, and accomplished a perfect blending of object, sign and colour. He painted using acrylics, which permitted greater spontaneity and freedom. His interest was captured by Rues de Paris with their animation and by les Halles, which led to the series Bouchers. La voiture de fleurs et le boucher (Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris) illustrates this new style, in which colour stains erase the precision of line and detail while the imaginary gains ground with characters that are simultaneously real and imagined. In 1966 a new series of Rues led to Triptyque du Dragon, exhibited at the Galerie du Dragon in 1967.

From 1951 onwards, Hélion’s work was the subject of regular exhibitions, often with accompanying texts by his poet friends.

Abroad: 1951 Hanover Gallery, London, paintings from 1947 to 1951, text by Francis Ponge; Sala degli Specchi, Venice, paintings from 1928 to 1951, presentation by Peggy Guggenheim, text by Christian Zervos; Galleria Del Millione, Milan, recent works, text by Christain Zervos; 1964 Gallery of Modern Art, New York, paintings from 1928 to 1964, texts by Pierre Bruguière and Christian Zervos. 1965 The Leicester Galleries, London, paintings from 1929 to 1965, text by Pierre Bruguière.

In Paris: 1953 Chez Mayo; in 1956, Galerie des Cahiers d’Art, where he showed his recent works in 1958 and 1961. 1962 Galerie Louis Carré, Peintures de 1929 à 1939, text by Raymond Queneau. 1964 Galerie Yvon Lambert, Trente ans de dessins, text by Francis Ponge. 1966 Galerie du Dragon, Peintures de 1937 à 1966, texts by Jean-Pierre Burgart, Pierre Bruguière, A. du Bouchet, Alain Jouffroy, Francis Ponge, Pierre Schneider and Christian Zervos.

Refusing to divorce himself from realism, he continued his series inspired by news items: he drew the events of May 1968, which he experienced as a meticulous observer on the barricades, filling a number of sketch books entitled Choses vues en Mai. He also drew circus performers at the Cirque d’Hiver. He resumed his series of street scenes: entrances to the metro or sometimes its corridors, second-hand clothes shops, couples on benches and amateur street orchestras (1971–1972). In May 1973 he settled permanently at Bigeonnette, where he painted the cabbages in his kitchen garden and the market stalls at Châteauneuf-en-Thymerais. In 1975, during his annual stay on Belle-Île, he made studies of lobsters and the wholesale fish merchants: these gouaches served him for the oils and pastels executed the following year. Periods of creative activity were interspersed with trips abroad that provided inspiration for his work: in 1976 New York inspired the series New York Scène. He was captivated by many different aspects of daily life: roadworks, café terraces, urinals and flea markets, to name a few. From 1981 Hélion’s eyesight began to deteriorate. He returned to his early subjects and painted large canvases. In a simplified style, employing a riot of colours, he remained faithful to his figurative investigation, which he described as follows:

“From 1925 to 1929: forceful painting with an instinctive reaction to nature and the object.

From 1929 to 1933: development of a system of signs.

From 1934 to 1939: attempt to express myself and the world through abstraction.

In 1939 and from 1943 to 1946: attempt to change the surrounding world with my abstract structures.

From 1947 to 1951: search for visual and human archetypes.

From 1951 to 1954: attempt to express everything through close contact with the object. Attempt to include appearance in the essence.

From 1955 to 1958: light.

After 1958: free. Everything at once” (op. cit.).

With his singular career, Hélion was considered a ‘revolutionary’ by his admirers.

He participated in the Salon de Mai from 1947 to 1949 as well as in 1957 and 1958.

In 1975 the Galerie Karl Flinker in Paris inaugurated its series of exhibitions of the artist with: Cinquante ans de peintures 1925–1975. Catalogues.

1986 Hélion, les années 60. Galerie Karl Flinker. Catalogue.

From 1970 to 1971 the first retrospective of Hélion’s work was held at the Grand Palais in Paris. Cent tableaux. 1928–1970. Catalogue. Archives de l’Art Contemporain.

At the same time, the Maison des Jeunes et de La Culture de Paris showed 40 ans de dessins 1930–1970. Catalogue. A travelling exhibition organised by the Centre National d’Art Contemporain was shown in 15 French museums. Catalogue.

Among the exhibitions and tributes we should mention:

1978 L’œuvre figuratif de 1928 à 1978. Musée Ingres, Montauban. Catalogue. Texts by A. Jouffroy, B. Noël, Fr. Ponge and J. Hélion.

1979 Dessins 1930–1978. Travelling exhibition organised by the MNAM Pinacothèque Athens. Catalogue Pontus Hulten and Daniel Abadie. At the Musée de Rennes in 1980.

1979 Peintures et dessins 1929–1979. Musée d’Art et d’Industrie, Saint-Etienne. Catalogue, text by Richard Crevier.

1980 Retrospective in Peking, Shanghai and Nanchang.

1984–1985 Hélion, peintures et dessins 1925–1983. Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Catalogue. Also shown in Munich and Lisbon. Texts Pierre Bruguière and Anne Moeglin-Delcroix. Complete biography and bibliography.

1987 Hélion, peinture de 1929 à 1983. Galerie Louis Carré, Paris. Catalogue.

1988 Hélion. Campredon, L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue. Catalogue.

Hélion’s work is present in many museum collections in France and abroad, in particular Paris: Musée National d’Art Moderne (Centre Georges Pompidou), where a Hélion room was opened in 1986 – Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; as well as Grenoble – Beauvais – New York – Philadelphia – Buffalo – Saint Louis – San Francisco – Chicago – Liège – Venice – Tel-Aviv – London.

- Pierre Bruguière: Jean Hélion. SPEI, Paris, 1970.

- René Micha: Jean Hélion, Flammarion, 1979.

- Journal d’un peintre (notebooks 1929–1984, preserved at the BN), A. Dimanche, Marseille, 1987.

- Henri-Claude Cousseau: Jean Hélion, Editions du Regard, Paris, 1992.